The widespread adoption of AI systems for information seeking has raised concerns about their potential impact on democracy. Many people worry that biased or ‘hallucinated’ outputs could misinform voters or distort public opinion. But there has been little empirical evidence on whether those fears are justified.

Our new paper is an attempt to fill this gap. We asked whether people in the UK use AI to obtain information about politics and current affairs – and tested how doing so affected their knowledge of key issues.

We found that as the UK went to the polls last summer, around one in eight voters turned to AI chatbots for answers. But despite widespread fears, we find little evidence that conversational AI makes people less informed. In fact, people who used chatbots to look up political issues became more knowledgeable, to roughly the same extent as those who used traditional search engines.

Why it matters

Unlike search engines, which provide a list of diverse information sources, AI chatbots respond with a single, fluent answer. Those answers can be useful, but chatbots often also produce incorrect or misleading outputs. Many worry that as voters increasingly turn to AI instead of search engines, they could end up with narrower, or unreliable perspectives on current affairs or political issues.

The stakes are especially high during election periods, when the information people consume may shape their voting choices. If chatbots were to promote misinformation or political bias at scale, widespread use could impact electoral outcomes and erode trust in democracy. However, despite intense speculation about these risks, empirical evidence about actual usage patterns and effects on political beliefs is hard to come by.

Do people use AI to research political issues?

To understand the scale of AI use for seeking information about political issues, we conducted a large-scale, representative survey of 2,499 UK adults around the time of the 2024 UK General Election. We found conversational AI was already a meaningful source of political information: 32% of chatbot users - equivalent to 13% of all eligible UK voters - reported using AI chatbots to seek out information directly relevant to their electoral choice.

Does AI make people more or less informed?

Next, we tested how using AI affected people’s knowledge of political issues. We recruited 2,858 UK participants and ran a series of randomised controlled trials.

First, participants reported their baseline beliefs claims about four political issues: immigration, climate change, criminal justice reform, and vaccines. Some of these claims were true, others false misinformation. Participants then used either a chatbot or a search engine to research two of these topics (randomly chosen). Afterwards, we reassessed their beliefs.

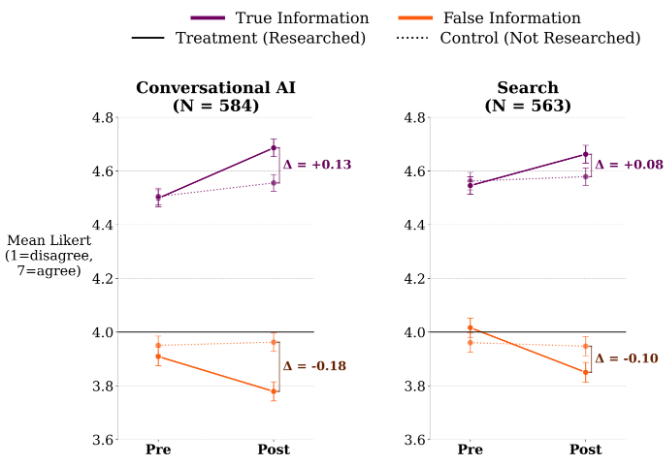

Contrary to widespread concerns, we found that using conversational AI did not degrade participants’ knowledge of political issues. Instead, knowledge increased on researched topics – to almost exactly the same extent for conversational AI and internet search. In other words, chatbots left people better informed, not worse. This was the case for all four political issues and even remained true when chatbots were prompted to be more persuasive.

In the visualisation below, we plot our results on a 7-point scale (1=disagree, 7=agree). It shows that belief in true information increases (purple lines) and belief in false information decreases (orange lines) from before to after research, especially for those topics researched (full lines). However, this occurs to the same extent for conversational AI (left plot) and internet search (right plot).

Future research directions

We recognise that our findings have limits. We sampled participants from just one country, during a single election, using a handful of AI models in short sessions. Future research could broaden our scope to include multiple countries and a wider set of models or track long-term effects. We also recognise that model behaviours change with each new release, and so it is possible that the patterns observed here will be different in the future. Though AI models do not yet appear to be driving belief in misinformation, other AISI research suggests that persuasive capabilities in AI models are improving, meaning vigilance will be required to monitor their real-world impacts.

Overall, our findings suggest that widespread concerns over the impact of chatbots on politics and elections may be somewhat exaggerated. Whilst it is true that AI outputs are sometimes factually incorrect, and it is always advisable to check alternative sources of information where possible, current evidence shows little indication that the transition to AI as a major source of political information will lead to a widespread degradation of political knowledge.

For more details, read the full paper.