The rapid growth of AI capabilities and increasing cross-economy adoption, have sparked widespread discussion about the future impacts of AI on global economies and labour markets.

There is great uncertainty about how AI will affect the UK labour market, and researchers are using a range of approaches aiming to answer this question. At the AI Security Institute (AISI), we’ve piloted an independent study targeted at a representative sample of the UK workforce. The research expands on the existing literature by creating a suite of generalisable benchmarks based on the O*NET taxonomy, and testing these in a controlled setting with human participants. This approach underpins a new framework for generating economy-wide impact estimates grounded in robust experimental data.

The UK Government recently announced the establishment of a comprehensive AI and the Future of Work Programme to ensure the UK is prepared to benefit from and adapt to the profound changes AI will bring to jobs, workers, and the labour market. This includes launching a new cross‑government AI and the Future of Work Unit and appointing an independent Expert Panel drawn from industry, academia, civil society and trade unions to guide this work.

The study described in this blog post represents an early output from this new Unit’s AISI-based research arm.

Our Research Design

In the occupation automation literature jobs are often understood as bundles of tasks, some of which are common across different professions. This is formalised in the Occupational Information Network (O*NET), a comprehensive occupational taxonomy developed by the U.S. Department of Labour.

For the purposes of the pilot study, we use the O*NET Generalised Work Activities. These represent the clearest examples of job behaviours common across occupations, for which it would be feasible to design experimental tasks.

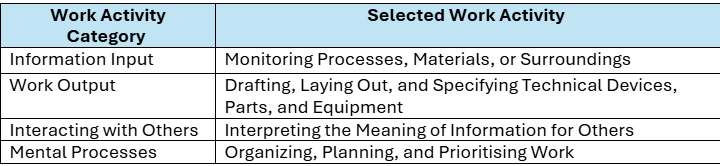

The generalised Work Activities are organised into 4 main categories: Information Input, Work Output, Interacting with Others, and Mental Processes. Given the necessarily limited scope of the pilot, we select from each category the Work Activity that is present across the greatest number of O*NET professions, shown in Figure 1. This gives the best balance between feasibility and drawing meaningfully generalisable conclusions.

We designed experimental tasks to simulate real-world scenarios where these Work Activities would be deployed, without requiring domain-specific knowledge to carry out the task. This ensures that tasks are applicable across multiple professions. We worked with the Institute for the Future of Work (IFOW), their academic network, and experts from Educate Ventures to design and validate the tasks for this experiment.

For the pilot phase of this research we aim to answer a key question: “To what extent does AI deliver productivity gains for individuals performing work-related tasks?”.

To isolate and measure these productivity gains, we use a randomised controlled trial (RCT) methodology. This approach selects two comparable groups from the same population and assigns a single intervention – in this case, access to a state-of-the-art large language model, released in early 2025 – to one group but not the other. Any subsequent differences we observe in outcomes can therefore be attributed to receiving the intervention.

We randomly assigned these four tasks across 500 participants recruited via Prolific. Participants were then randomly allocated to either the Treatment (access to AI tools) or the Control (no access to AI tools) groups, and received a short tutorial on how to use the research platform functionalities and tooling available to them.

Results

All participant responses were graded using bespoke AI autograders calibrated to task-specific rubrics. A subset of responses from both Treatment and Control groups were graded by humans, with strong agreement between human and AI graders for Task 1, 2, and 4, and slightly weaker agreement for Task 31.

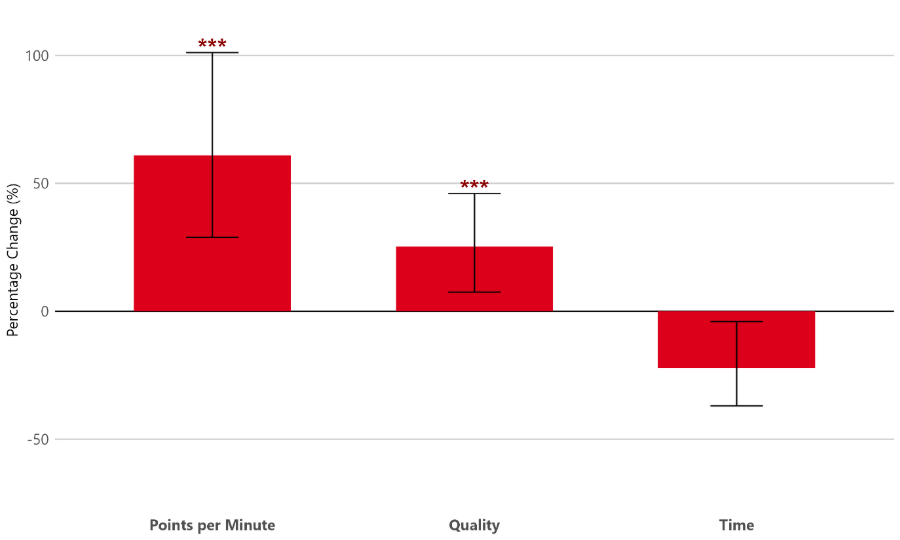

For all participants we measure 3 outcome variables:

- Quality: The total score achieved on a task.

- Time: The total time taken to complete a task.

- Points per Minute: : a single productivity measure that divides the task score by the time taken. This assumes every extra minute adds the same amount of quality to an output (e.g. a score of 10 in 5 minutes is as good as a score of 20 in 10 minutes).

Figure 2 shows the average percentage change in outcome of the Treatment Group relative to the Control Group that is due to AI use. The bars represent the magnitudes across the 3 respective outcome measures, with stars denoting the statistical significance of the estimates (*** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1). Outcome variables are transformed from a log scale to percentage changes. For Points per Minute and Quality Measures we would expect to see values greater than 0, in other words both measures are expected to improve with AI use. For Time we would expect to see a value below 0, in other words the Treatment Group performed tasks faster than the Control Group.

On average across the 4 tasks, we observe 25% higher points scored for participants in the Treatment groups, relative to their Control group counterparts, as well as 61% more Points per Minute. However, we do not see statistically significant differences between the 2 study groups in the time they took to complete the tasks.

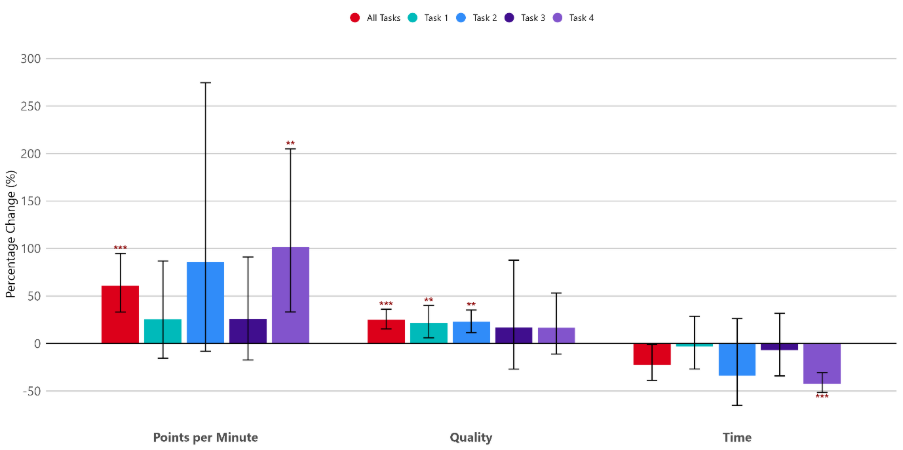

Decomposing the results by task, we observe variation in the impacts that AI augmentation has on participant productivity.

Task 1 (Monitoring Processes, Materials, or Surroundings): AI use provides significant uplift in task Quality (22%) but does not impact Time or Points per Minute.

Task 2 (Drafting, Laying Out, and Specifying Technical Devices, Parts, and Equipment): We observe very similar results to Task 1, with AI providing a 23% uplift on task Quality, but none on our other metrics.

Task 3 (Organising, Planning, and Prioritising Work): This is the only task where we do not observe any statistically significant uplift on any of our metrics.

Task 4 (Interpreting the Meaning of Information for Others): For this task, we see the inverse of our results for Tasks 1 and 2 – AI use does not improve the Quality of performance but does improve Time (-42%) and Points per Minute (+102%).

Decomposing the productivity impacts by task reveals the jagged capabilities of AI systems. Tasks 1, 2, and 4 all require some analysis, synthesis, and interpretation of data to answer close-ended questions – a domain in which we know AI systems excel. In contrast, Task 3 requires a more subjective and open-ended output, asking participants to produce forward-looking strategic proposals. While AI capabilities in this domain continue to improve, they still lag behind the more structured requirements present across the other tasks.

Due to our limited sample size, we have a high degree of uncertainty around all of our estimates (though they are broadly in line with other results found in the wider literature. As such, these results should be treated as preliminary indicators. Further analysis is required to establish greater confidence in the magnitude of impact across all three productivity measures.

Next Steps

Our results suggest that AI could provide productivity gains for a significant number of workers across the UK; the 4 Work Activities we chose are present across all 412 SOC2020 occupational groups8. However, we cannot say for sure whether these isolated impacts will drive substantial productivity improvements at the overall occupation level.

We are building on the success of the pilot study, with work underway to expand the suite of Work Activities tested under this framework. This will enable us to build on our initial findings and provide comprehensive evidence on AI-driven productivity gains across the UK labour market. Furthermore, we plan to benchmark the performance of state-of-the-art AI system by testing agentic system capabilities on these tasks, with minimal human input. This will aim to address a key gap in the current literature by generating experimental evidence on the exposure of tasks, and therefore occupations, to automation across the UK economy.

As the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology launches the AI and the Future of Work Unit, this research exemplifies the evidence-led approach at the heart of our mission. Our goal is to ground policy in robust experimental data, allowing us to anticipate disruption, harness productivity gains, and ensure the UK is prepared for the opportunities and challenges of AI-driven change.

Acknowledgements

This research was conducted in collaboration with the Institute for the Future of Work, Educate Ventures, Frontier Economics, Revealing Reality, Prolific, and Faculty AI – with special thanks to Abby Gilbert, Rose Luckin, Benedict du Boulay, Noa Sher, Madiha Khan, Ali Chaudhry, Jolene Skordis and Arjun Ramani.

1. Krippendorff’s Alpha Statistics: Task 1 (α= 0.822), Task 2 (α= 0.919), Task 3 (α= 0.693), Task 4(0.841)