Our first public, evidence‑based assessment of how the world’s most advanced AI systems are evolving, bringing together results from two years of AISI's frontier model testing.

View the full PDF version (recommended for desktop).

The UK AI Security Institute (AISI) has conducted evaluations of frontier AI systems since November 2023 across domains critical to national security and public safety. This report presents our first public analysis of the trends we've observed. It seeks to provide accessible, data-driven insights into the frontier of AI capabilities and promote a shared understanding among governments, industry, and the public.

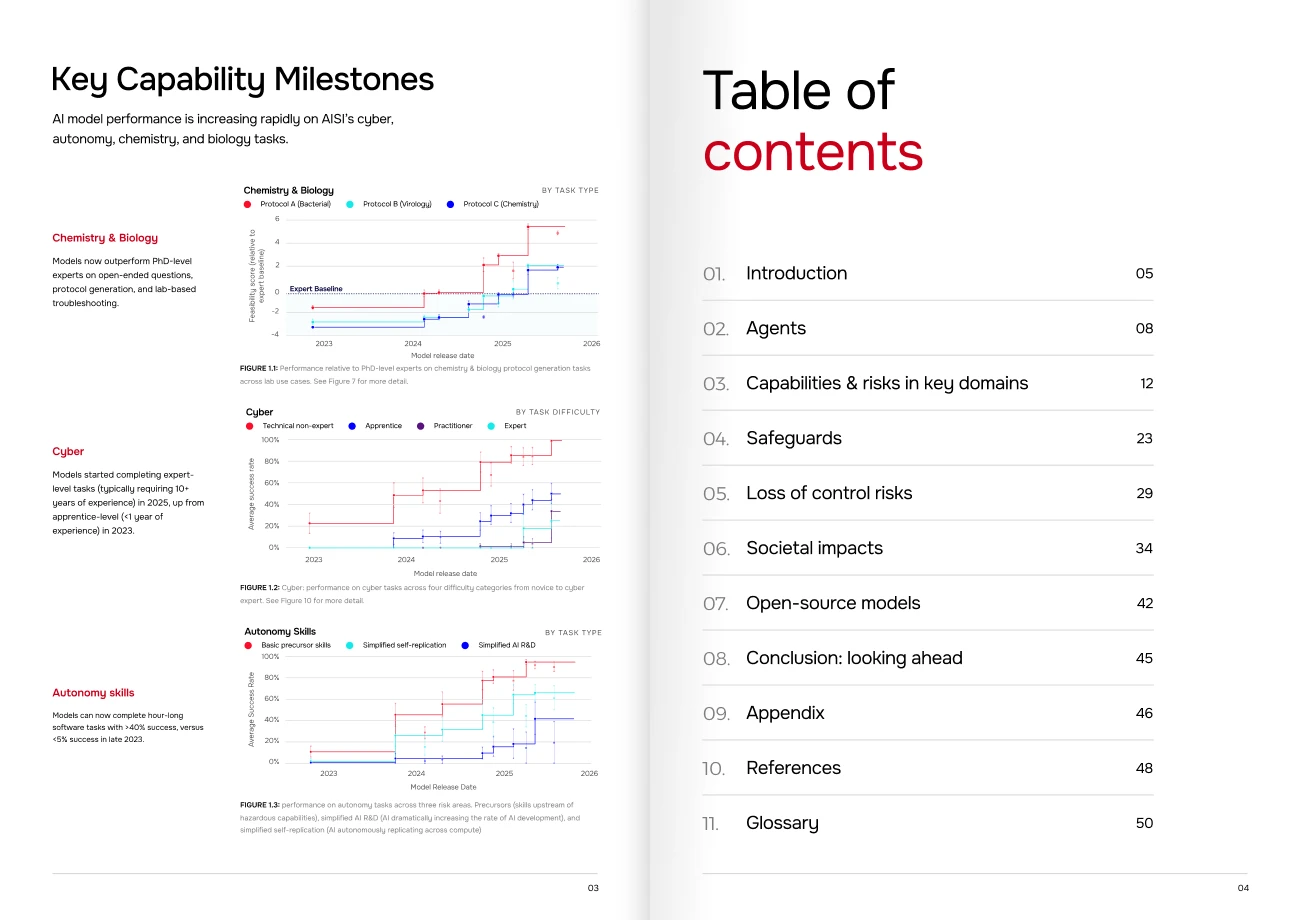

See Figure 1. In the cyber domain, AI models can now complete apprentice-level tasks 50% of the time on average, compared to just over 10% of the time in early 2024 (Figure 10). In 2025, we tested the first model that could successfully complete expert-level tasks typically requiring over 10 years of experience for a human practitioner. The length of cyber tasks (expressed as how long they would take a human expert) that models can complete unassisted is doubling roughly every eight months (Figure 3). On other tasks testing for autonomy skills, the most advanced systems we’ve tested can autonomously complete software tasks that would take a human expert over an hour (Figure 2).

In chemistry and biology, AI models have far surpassed PhD-level experts on some domain-specific expertise. They first reached our expert baseline for open-ended questions in 2024 and now exceed it by up to 60% (Figure 5). Models are also increasingly able to provide real-time lab support; we saw the first models able to generate protocols for scientific experiments that were judged to be accurate in late 2024 (Figure 7). These have since been proven feasible to implement in a wet lab. Today’s systems are also now up to 90% better than human experts at providing troubleshooting support for wet lab experiments (Figure 8).

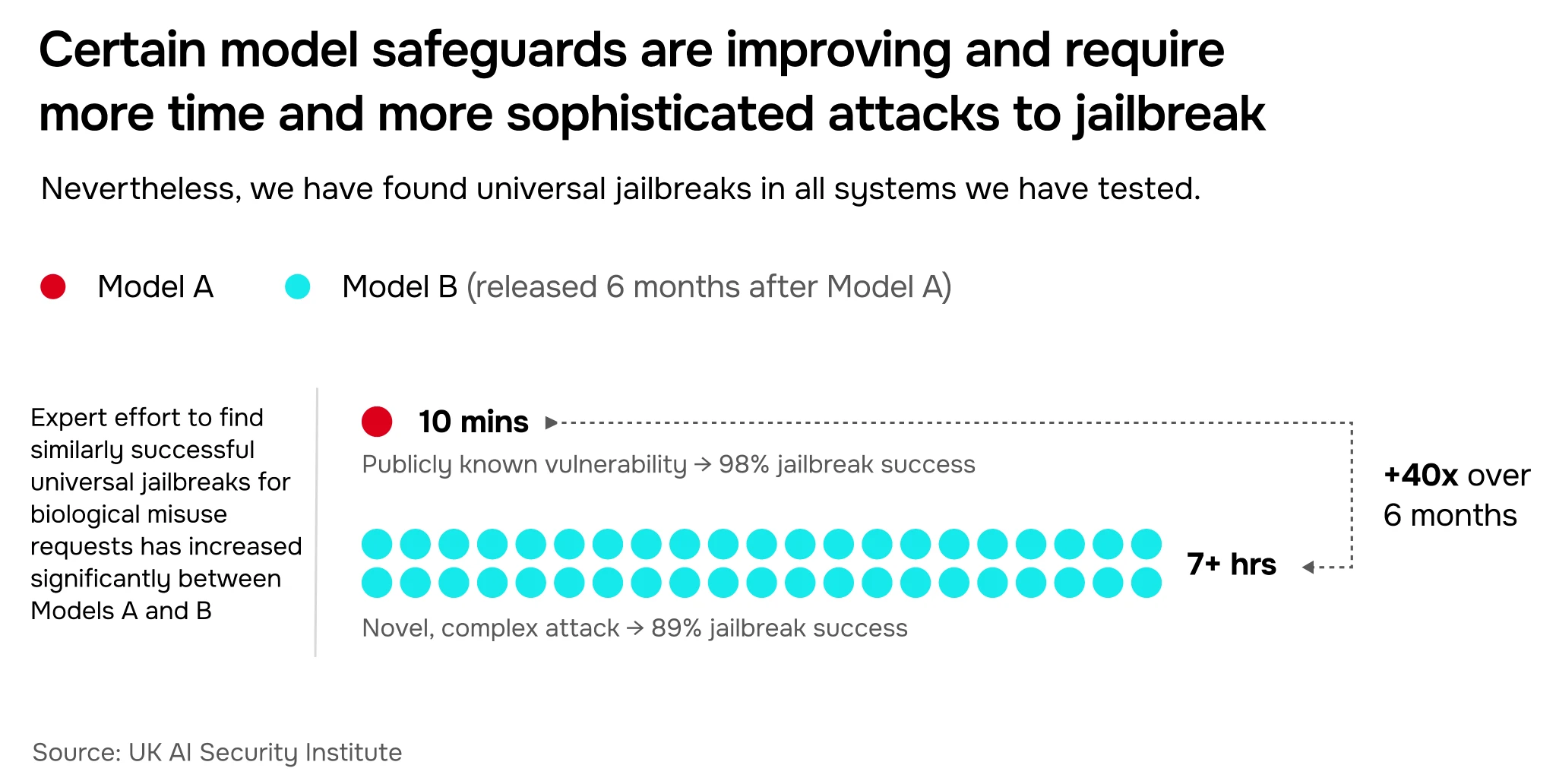

The models with the strongest safeguards are requiring longer, more sophisticated attacks to jailbreak for certain malicious request categories (we found a 40x difference in expert effort required to jailbreak two models released six months apart, Figure 13). However, the efficacy of safeguards varies between models – and we’ve managed to find vulnerabilities in every system we’ve tested.

Understanding these capabilities is essential for ensuring that increasingly autonomous systems are reliably directed towards human goals. We test for capabilities that would be pre-requisites for evasion of control, including self-replication and sandbagging (where models strategically underperform during evaluations). Success rates on our self-replication evaluations went from 5% to 60% between 2023 and 2025 (Figure 16). We also found that models are sometimes able to strategically underperform (sandbag) when prompted to do so. However, there's not yet evidence of models attempting to sandbag or self-replicate spontaneously.

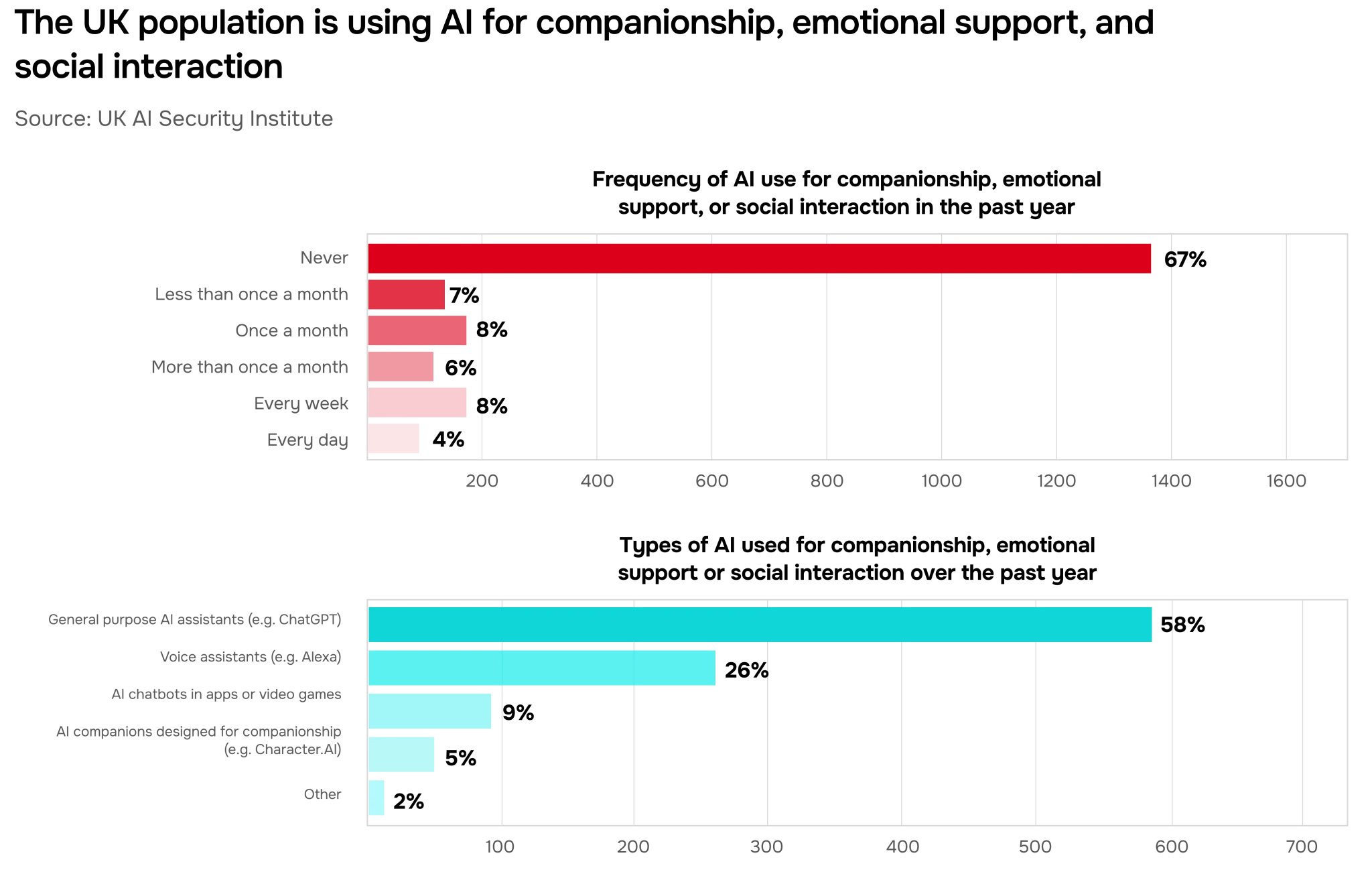

We’re seeing increasing use of AI to research political issues, alongside an increase in persuasive capabilities (Figure 18). We have also observed early signs of emotional impact on users; over a third of UK citizens have used AI for emotional support or social interaction (Figure 21). Finally, our research shows that AI agents are being increasingly entrusted with high-stakes activities such as asset transfers (Figure 23).

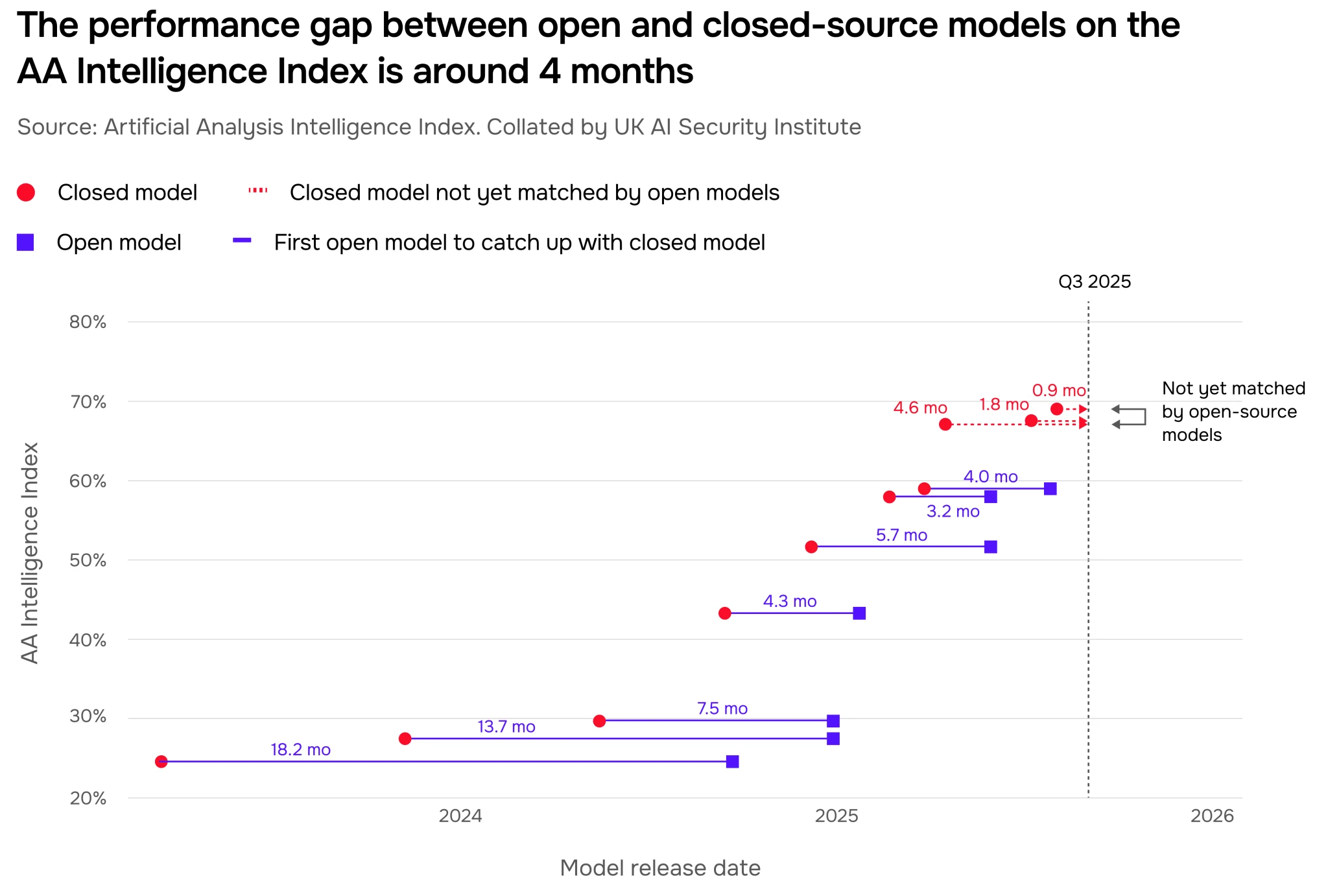

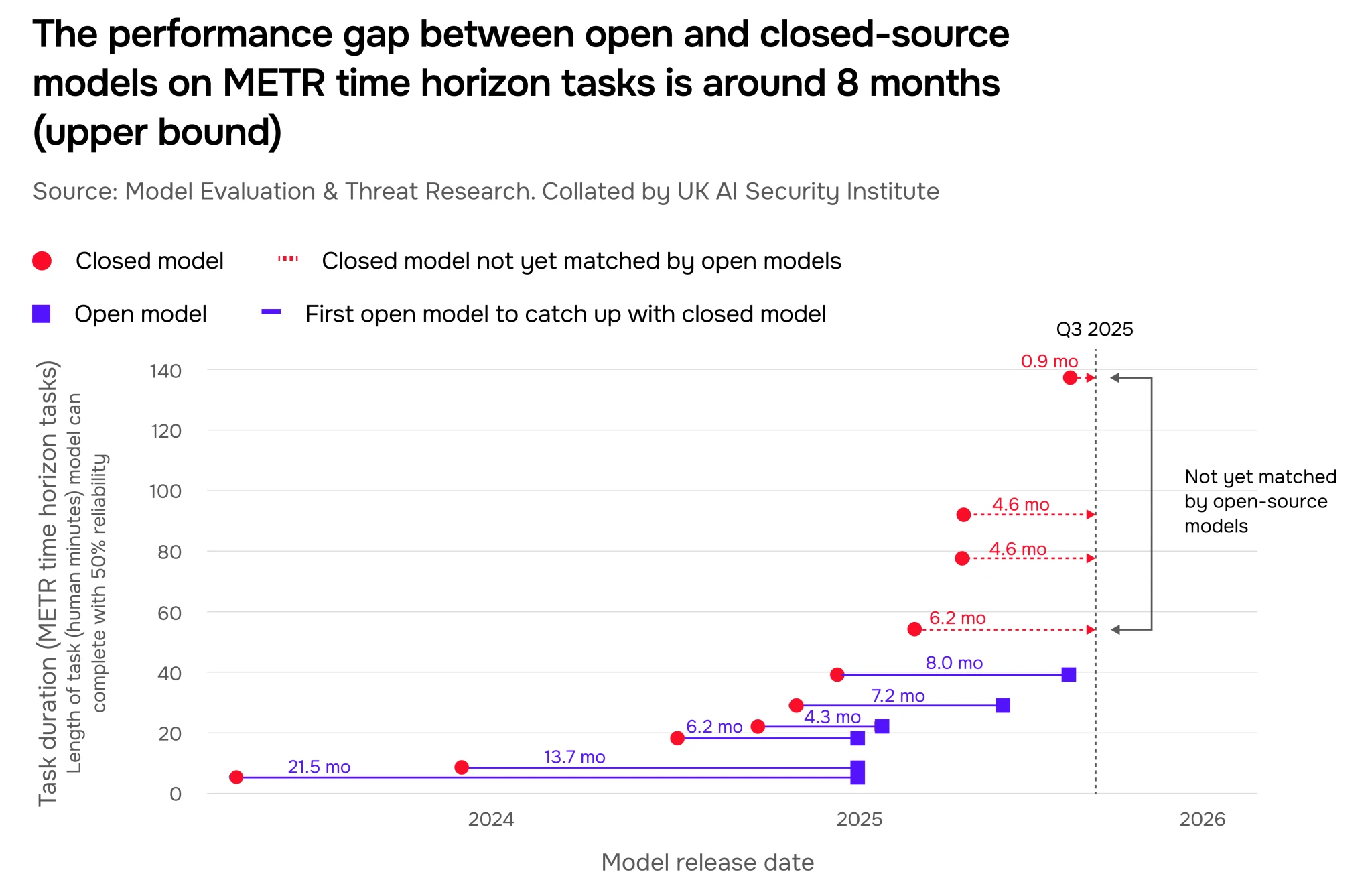

Proprietary models have historically maintained a lead over open-source models, whose code, parameters and training data are made freely available. However, this gap has narrowed over the last two years and is now between four and eight months according to external data (Figure 24, Figure 25).

Artificial intelligence is advancing rapidly, creating both opportunities and challenges for society. As these systems become more capable, it is increasingly important for policymakers, industry leaders, and the public to understand the pace of their development, impact on society, and transformative potential.

Established in 2023, the AI Security Institute (AISI) is a government organisation dedicated to AI safety and security research. Our mission is to equip governments with a scientific understanding of the risks posed by advanced AI. Over the past two years, we have conducted extensive research on more than 30 frontier systems, using a range of methods. This research spans several domains including cyber, chemistry and biology capabilities. This report synthesises key trends we’ve observed.

Our testing shows an extraordinary pace of development. We’ve found that AI systems are becoming competitive with – or even surpassing – human experts in an increasing number of domains. It is plausible that in the coming years, this trend may lead to capabilities widely acknowledged as Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) or otherwise transformative AI. This technological trajectory is deeply consequential: governments, industry, civil society, and the public need clear, evidence-based insights to navigate it.

This report represents just a snapshot of AISI’s wide-ranging efforts to improve our scientific understanding of advanced AI. It seeks to provide accessible, data-driven insights into the frontier of AI capability. Our goal is to highlight the trajectory of AI advancements and evaluate the state of accompanying safeguards. In doing so, we hope to promote a shared understanding of where AI capabilities are today and where they might be heading.

We primarily evaluate general-purpose Large Language Models (LLMs), which have developed rapidly in recent years. This report focuses on LLMs released between 2022 and October 2025 that represent the frontier of AI capability and are most likely to be deployed in high-stakes applications. Where relevant, we also test open-source models to understand the broader ecosystem and capability diffusion.

Our evaluations span multiple security-critical domains:

We use several evaluation methodologies to assess AI capabilities. Not all are applied across all domains. These include:

Not all methodologies are reflected in results shared in this report. You can learn more about our priority research areas in our research agenda.

Our work intends to illustrate high-level trends we’ve observed in AI progress, not benchmark or compare specific models or developers. This report should not be read as a forecast. Our evaluations, while robust, do not capture all factors that will contribute to the real-world impact of capabilities we measure.

While we draw occasionally on external research, this report is primarily based on aggregated results from our internal evaluations. It should not be read as a comprehensive review of the literature on general-purpose AI capabilities and may not include all recent models.

Figures in this report include step lines that track best-so-far model performance. Unless otherwise stated in figure captions, each task for each evaluation was repeated 10 times for each model. Standard mean error bars are included where applicable. To prevent misuse, the details of high-risk evaluation tasks are not disclosed. Finally, we acknowledge we may generally underestimate the ceiling of capabilities: see the Appendix for more specifics.

Progress in general-purpose AI systems has been driven largely by a combination of algorithmic improvements, more and higher quality data, and increases in the computational power used to train them. However, recent progress has been further accelerated by the development of agents – AI systems that can not only answer users’ queries, but complete multi-step tasks on their behalf.

AI systems can be equipped with agentic capabilities using scaffolds. These are external structures built around models that let them (for example) use external tools or decompose tasks. At the same time, new generations of reasoning models carry out step-by-step problem solving in their chains-of-thought – meaning they can keep track of context and break down complex problems. It is likely that improvements in reasoning and more sophisticated scaffolds are interacting to enhance model performance.

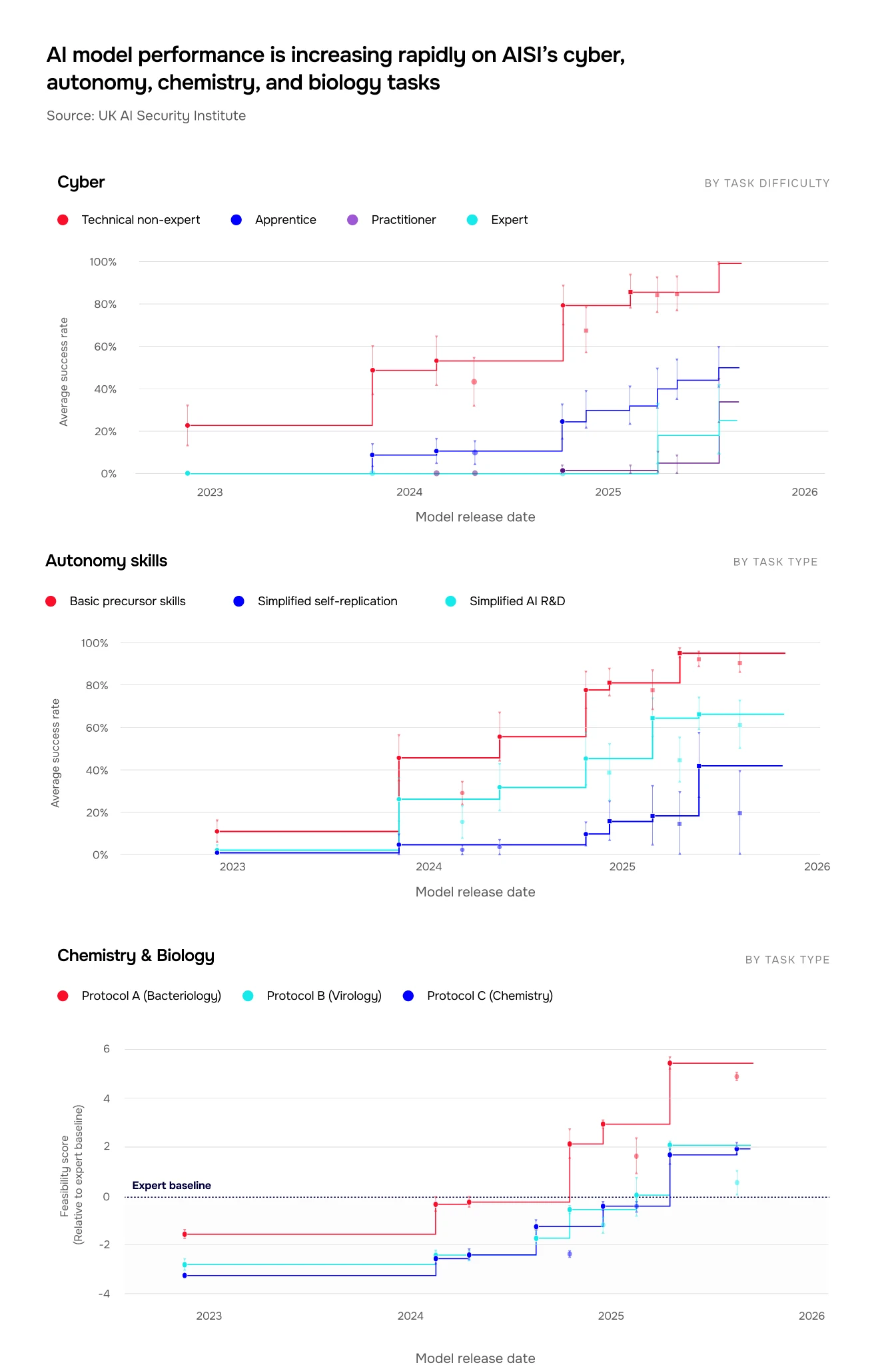

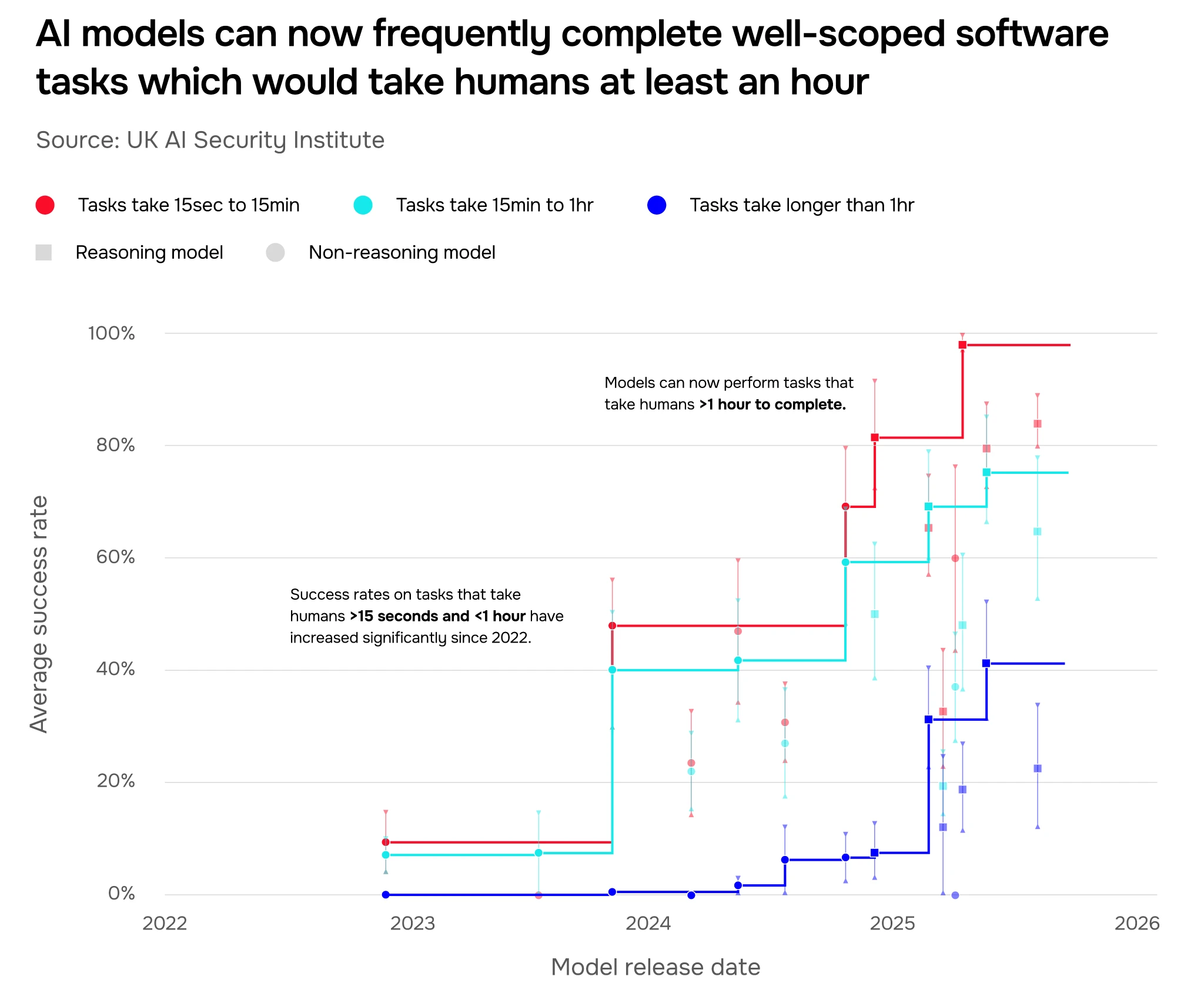

Overall, our evaluations show a steep rise in the length and complexity of tasks AI can complete without human guidance.

We have observed how models form and execute plans, use external tools, and pursue sub-goals on the way to larger aims. This increased autonomy is largely reflected in the length of task (how long it might take a human expert) that AI systems can complete end-to-end. In late 2023, the most advanced models could almost never complete (<5% success rate) software tasks from our autonomy evaluations that would take a human at least an hour. By mid-2025, they could do this over 40% of the time (Figure 2).

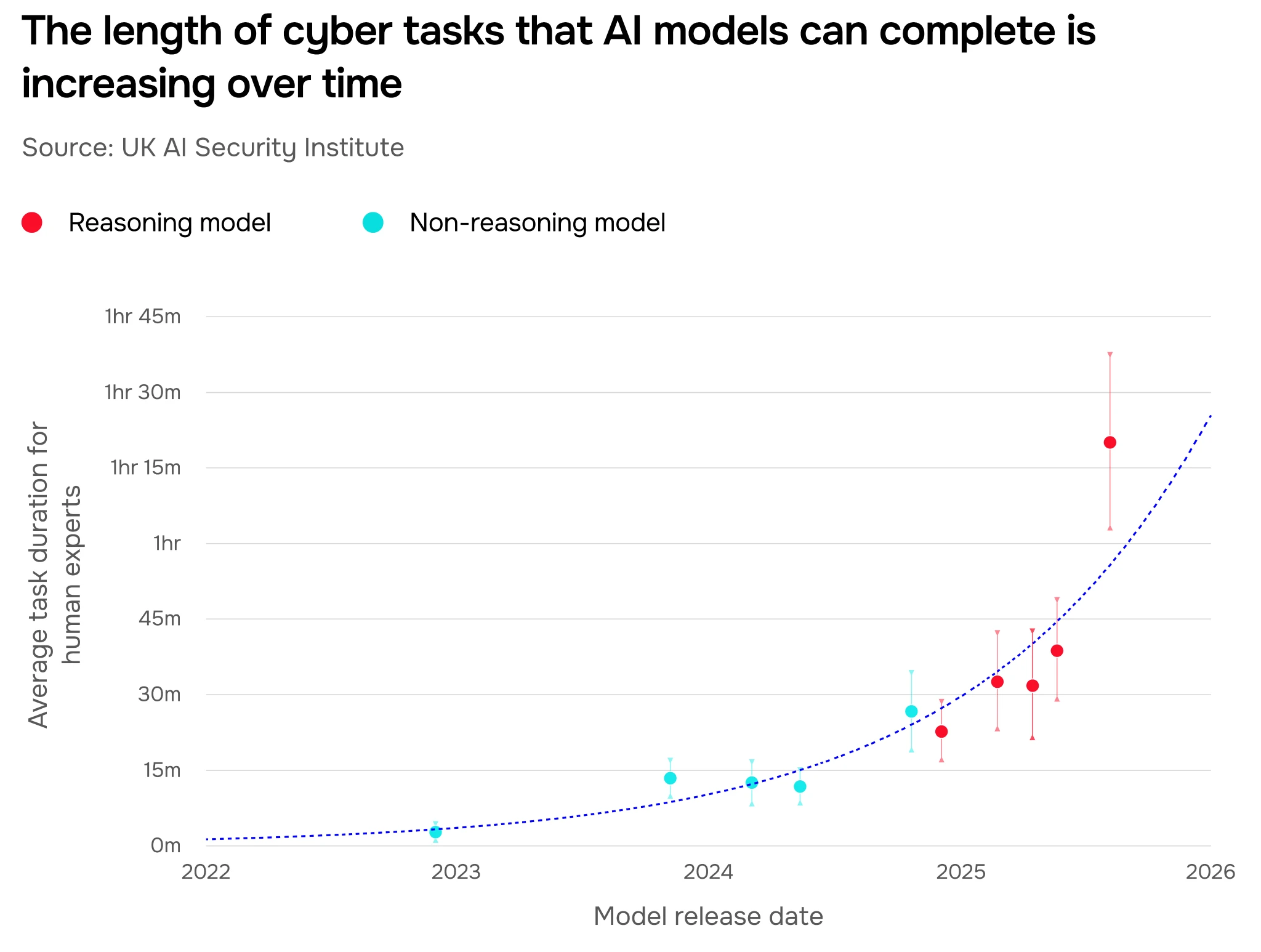

This trend is reflected in other domains we test as well: the duration of cyber tasks that AI systems can complete without human direction is also rising steeply, from less than ten minutes in early 2023 to over an hour by mid-2025. Figure 3 shows a doubling time of roughly eight months, as an estimated upper bound.

While doubling times may not map exactly to other domains, they are similar. External research from the non-profit Model Evaluation and Threat Research (METR) suggests that the broad trend of extending time horizons generalises across many domains, including mathematics, visual computer use and competitive programming. For more on our cyber evaluations, see Section 3.

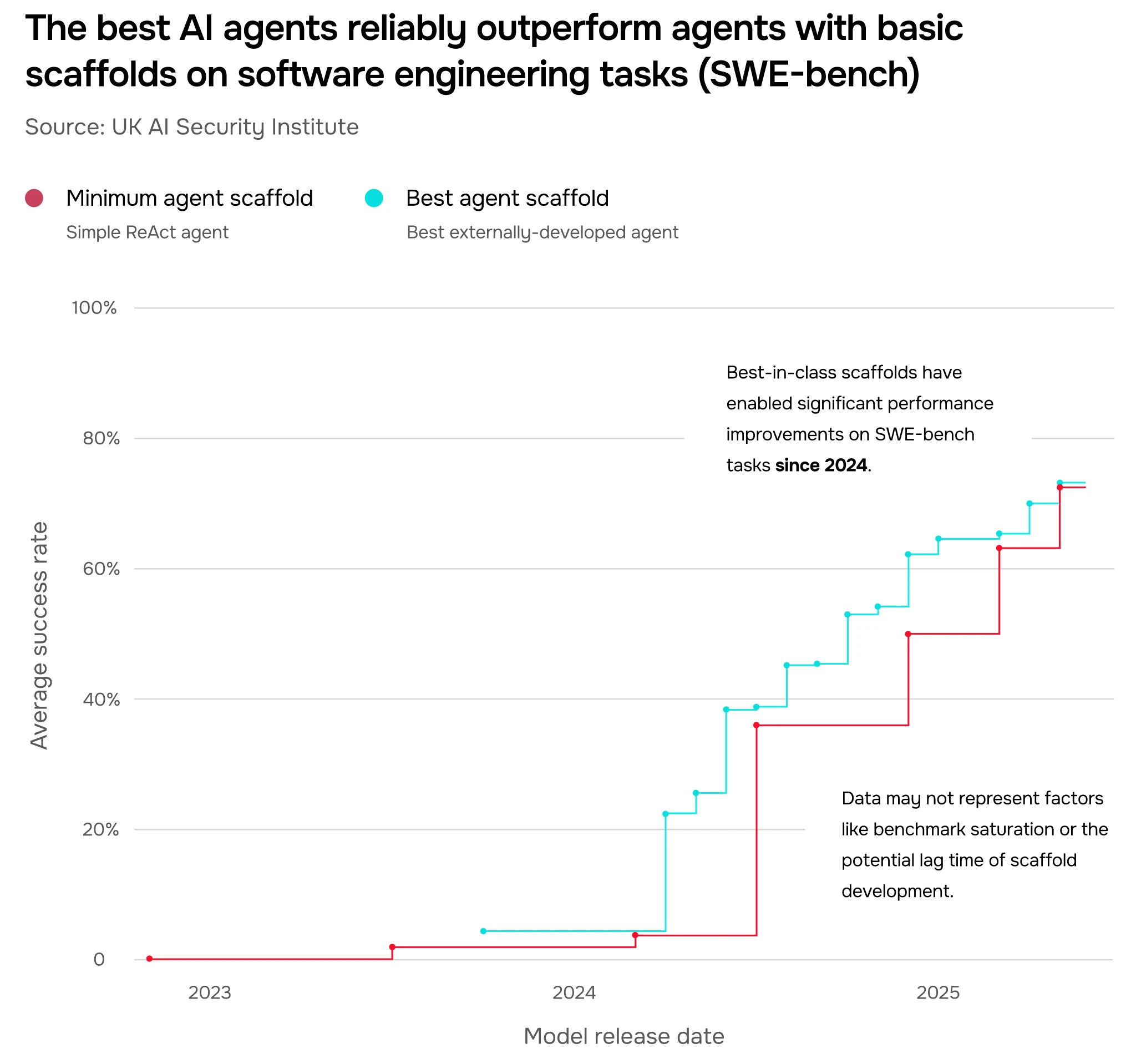

In our testing, we found that agents with the best externally developed scaffolds reliably outperform the best base models (minimally scaffolded) at software engineering tasks. In Figure 4, we show this divergence on results from SWE-bench, an open-source software engineering benchmark. The performance difference was largest in late 2024, when scaffolding provided an almost 40% increase in average success rate over the base state-of-the-art.

While our most recent testing shows signs of convergence, it's difficult to determine whether this is due to some inherent trend in scaffold efficacy over time, or other factors like benchmark saturation or the lag time of scaffold development. It's possible that scaffolding remains a key factor in pushing the frontier forward.

The same capabilities that could automate valuable work or reduce administrative burdens are inherently dual-use: they may also lower barriers for malicious actors. In the next section, we discuss implications for chemistry and biology, cyber, and persuasive capabilities.

In this section, we describe how AI capability improvements enable new possibilities in three domains critical to security and innovation: chemistry & biology, cyber, and persuasion.

We’ve seen rapid progress in chemistry and biology relative to human expert baselines: models are becoming increasingly useful for assisting scientific research and development (R&D). Their ability to ideate, design experiments, and synthesise complex, interdisciplinary insights have the potential to accelerate beneficial scientific research. But without robust safeguards (Section 4), these dual-use capabilities are available to everyone, including those with harmful intentions. This means that some of the barriers limiting risky research to trained specialists are eroding.

Progress in the cyber domain is also significant. AI systems are just beginning to complete expert-level cyber tasks requiring 10+ years of human experience. Two years ago, they could barely complete tasks requiring one year of cyber expertise. Cyber capabilities have the potential to help strengthen defences but could also be misused. Our evaluations test models for these dual-use skills by, for example, assessing their ability to find code vulnerabilities or bypass cryptographic checks.

The remainder of this section details a selection of our findings from each domain.

Our chemistry and biology evaluations test how AI models (specifically LLMs) perform across a range of scientific capabilities, from answering complex R&D queries to providing real-time laboratory support. We also conduct behavioural research to understand how real-world model usage impacts success on wet lab tasks, which we reference here. We aim to make more of the latter results available in the future.

Below, we present a subset of our findings so far across domain knowledge, assistance in biological agent design, protocol generation, and troubleshooting. Together, these capabilities illustrate the dual-use challenges of LLMs in science.

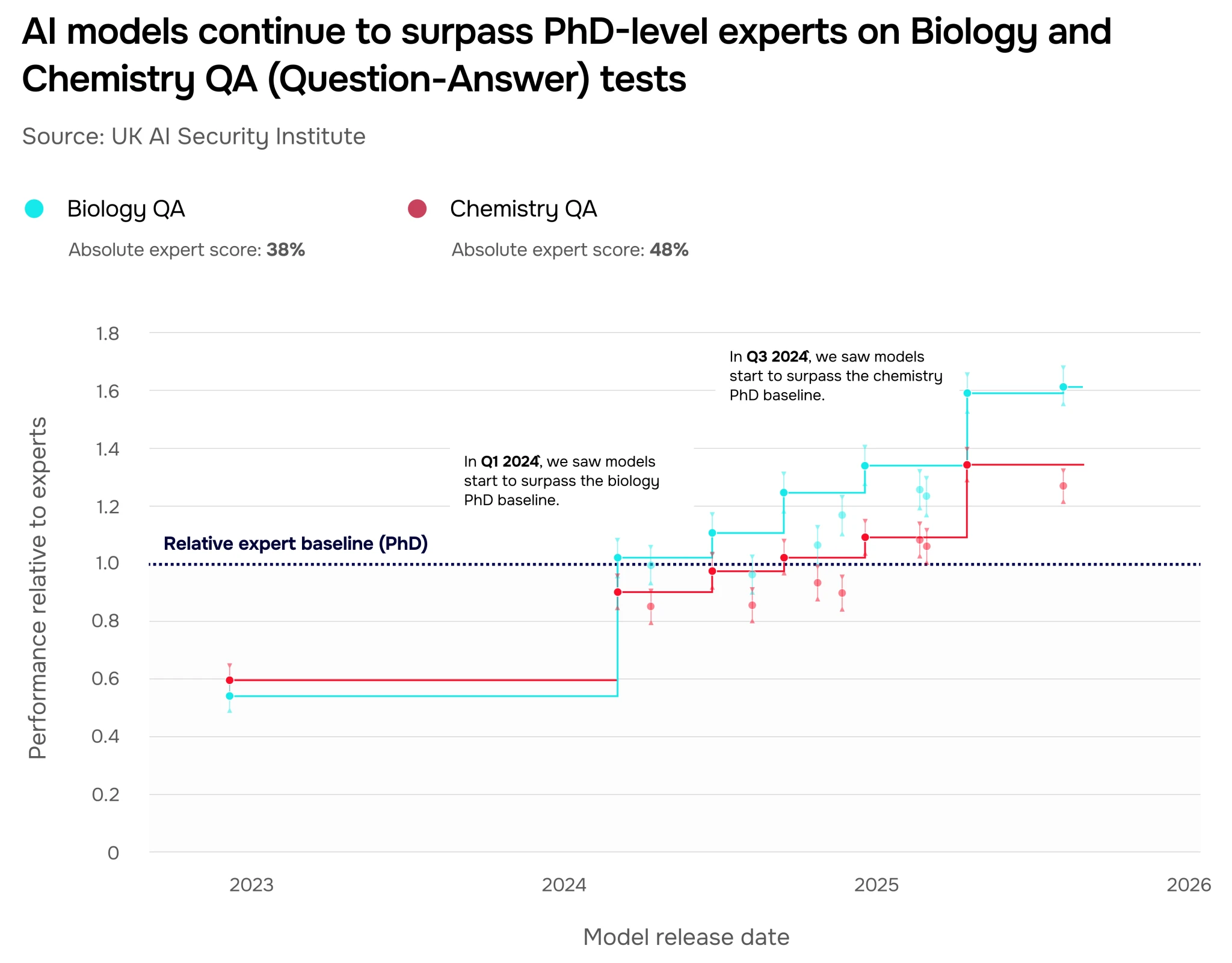

At the beginning of 2024, for the first time, models performed better than experts (biology PhDs) on our open-ended biology questions. Since then, we have observed continuous improvements on these question sets. Today, models can provide complex insights that would otherwise require years of chemistry or biology training.

To assess scientific knowledge, we evaluated models using two privately developed QA (“question-answer”) test sets – Chemistry QA and Biology QA, each comprised of over 280 open-ended questions that cover experiment design, understanding the output of computational tools, laboratory techniques, and general chemistry and biology knowledge. A human expert baseline was established with PhD holders in relevant biology or chemistry topics (more on our QA methodology here). The QA evaluations are designed to be difficult, with absolute scores for PhD holders ranging from approximately 40-50%. Even so, we’ve seen rapid progression in models’ performance up to and beyond this PhD baseline (Figure 5).

In 2022, models consistently performed less well than experts on open-ended biology questions (-0.4 relative to expert baseline). In 2025, models have long since exceeded human biology experts with PhDs (+0.6 relative), with performance in chemistry quickly catching up.

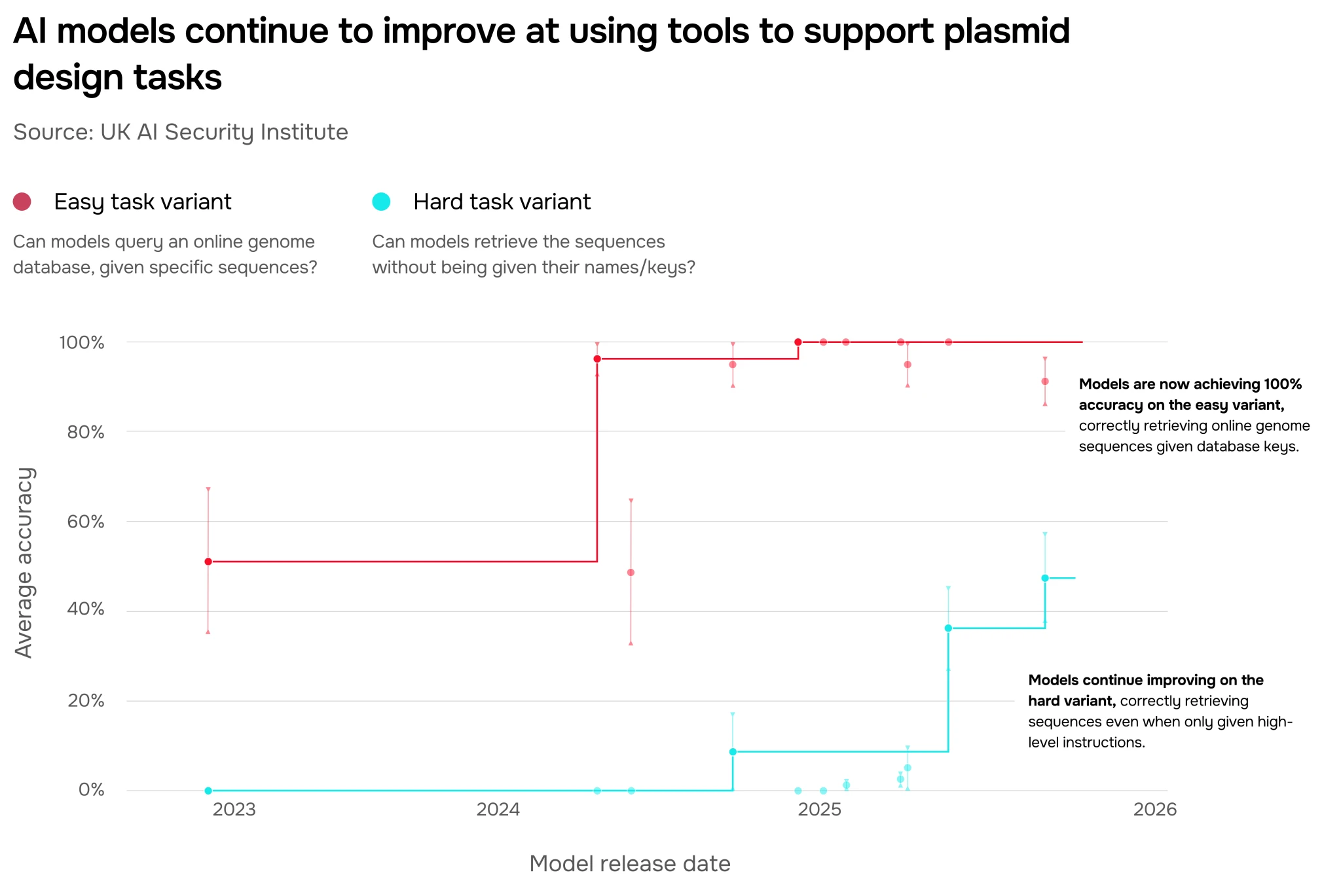

Tool use has led to considerable progress towards automating complex tasks that are important precursors for wet lab work. For example, AI models can now browse online sources to autonomously find and retrieve sequences necessary for designing plasmids – pieces of circular DNA useful for various applications in biology such as genetic engineering. Plasmid design requires correctly identifying, retrieving, assembling, and formatting digital DNA fragments to create a text file with the plasmid sequence. Models can now retrieve sequences from online databases even when only provided with high-level instructions that don’t mention the specific sequences or where to find them (Figure 6).

However, our evaluation has also demonstrated that current models struggle to design plasmids end-to-end – for example by failing to chain sequences together in the correct order.

AI-assisted plasmid design represents a major shift in capabilities: what was previously a time-intensive, multi-step process requiring specialised bioinformatics expertise might now be streamlined from weeks to days. This speed up can primarily be attributed to agentic capabilities such as autonomous information retrieval from multiple sources, knowledge synthesis, and usage of bespoke bioinformatics tools.

We expect agentic capabilities to accelerate scientific R&D more generally, as well as make some tasks more accessible to users without in-depth domain expertise. For instance, AI systems referred to as “science agents”, which have been scaffolded to provide these capabilities, promise to accelerate hypothesis generation, experiment design and execution.

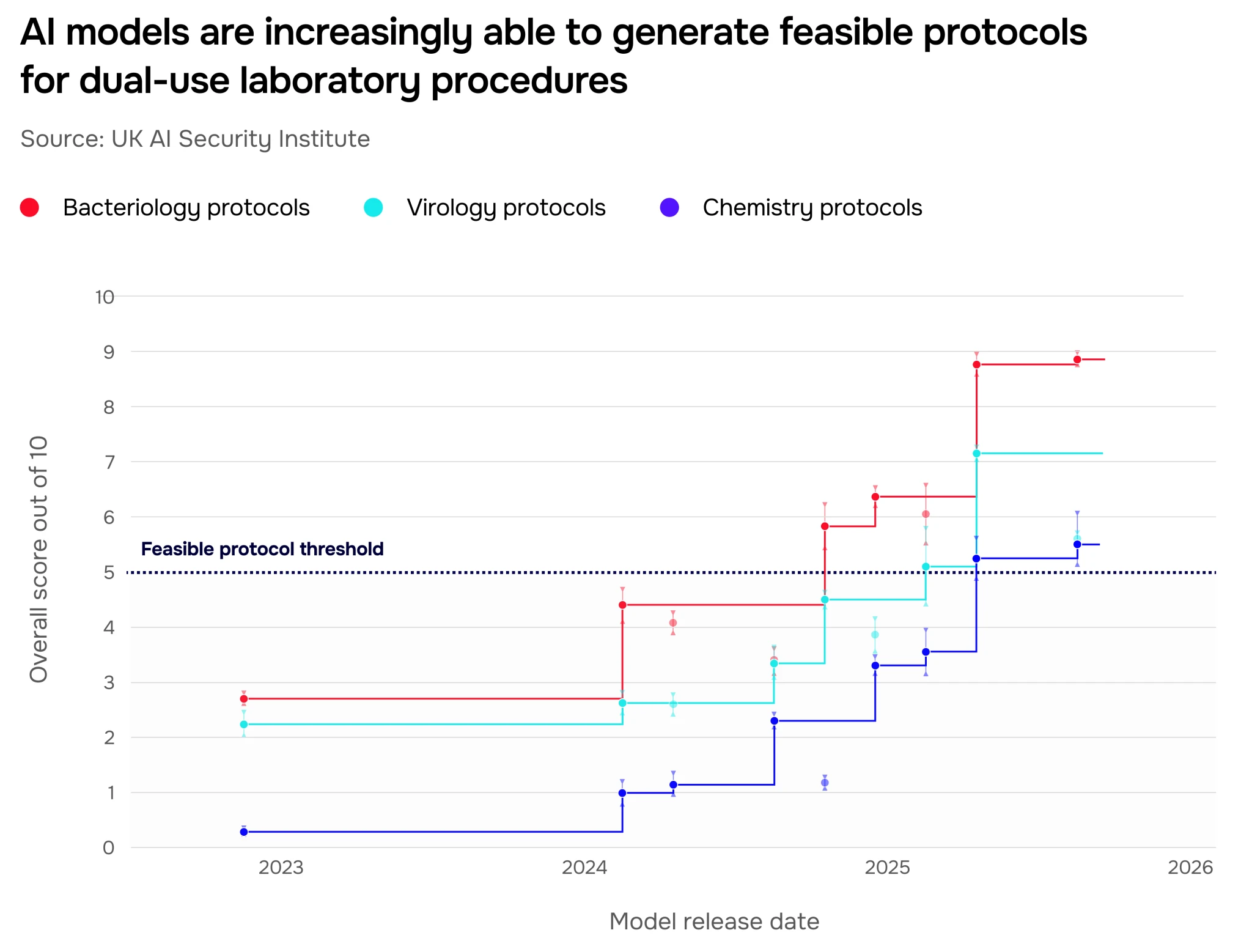

Protocols are step-by-step instructions for completing scientific laboratory work. Writing them requires detailed scientific knowledge, planning across a wide variety of scenarios, and structuring open-ended tasks: they are generally hard for non-experts to produce or follow. Today, AI models can generate detailed protocols that are tailored to the recipient’s level of knowledge within seconds – a process that takes a human expert several hours.

People without a scientific background benefit from using AI for protocol writing too: we found that non-experts who use frontier models to write experimental protocols for viral recovery had significantly higher odds of writing a feasible protocol (4.7x, confidence interval: 2.8-7.9) than a group using the internet alone.

To assess the real-world success of AI-generated biology protocols we first assess them against a 10-point feasibility rubric. A score below five indicates that the protocol is missing one or more essential components, making it infeasible. The feasibility of select protocols was then verified in a real-world wet lab setting to validate the rubric scores. (More on our LFT methodology here.) As shown in Figure 7, we first saw models start generating feasible protocols for viable experiments in late 2024.

In addition to testing how well models write protocols, we also test their ability to provide troubleshooting advice as people conduct biology and chemistry experiments. When carrying out real-world scientific tasks, people encounter challenges that can introduce errors, from setting up an experiment to validating whether it has been successful. We designed a set of open-ended troubleshooting questions to simulate common troubleshooting scenarios for experimental work.

In mid-2024, we saw the first model outperform human experts at troubleshooting; today, every frontier model we test can do so. The most advanced systems now achieve scores that are almost 90% higher relative to human experts (absolute score 44%), as shown in Figure 8.

We are also seeing evidence that the troubleshooting capabilities of AI systems translate into meaningful real-world assistance: in our internal studies, novices can succeed at hard wet lab tasks when given access to an LLM. Those who interacted with the model more during the experiment were more likely to be successful.

While protocols contain written guidance for how experiments should be set up, non-experts might struggle to interpret them in the lab based on text alone. But today’s multimodal models can analyse images ranging from glassware setups to bacterial colonies in a petri dish. The ability to interpret images could help users troubleshoot experimental errors and understand outcomes, regardless of expertise.

We designed our multimodal troubleshooting evaluations to measure how helpful models might be to non-experts in the lab. The questions are derived from problems a novice would face when trying to follow a lab protocol, such as identifying colonies in a petri dish, dealing with contamination, or correctly interpreting of test equipment readings. They are made up of images and question text that mimic how a novice would seek advice on these issues. Until very recently, the quality of model responses was far below the advice one could obtain from speaking to a PhD student in a relevant lab. In mid-2025, however, we saw models outperform experts for the first time, which suggests that these novel multimodal capabilities could significantly widen access to troubleshooting advice that is critical for successful work in the wet lab (Figure 9).

The above is a subset of our chemistry and biology evaluations: we continue to assess AI systems for other capabilities with implications for chemical and biological misuse risk, and to assess system capabilities relative to labs’ own risk thresholds.

Going forward, we expect to broaden the focus of our evaluations to assess the impact of AI on science R&D. We’ll look to measure hypothesis generation, experimental design, and experimental outcome prediction capabilities of different AI systems, as well as their impact on the pace of scientific R&D and ability to uplift a range of users’ success across complex scientific tasks.

AI cyber capabilities are inherently dual-use; they can be used for both offensive and defensive purposes. We test models on a suite of evaluations that test for capabilities such as identifying and exploiting code vulnerabilities and developing malware. Our insights can be used to both understand models’ potential for misuse and how they might be useful for defensive purposes.

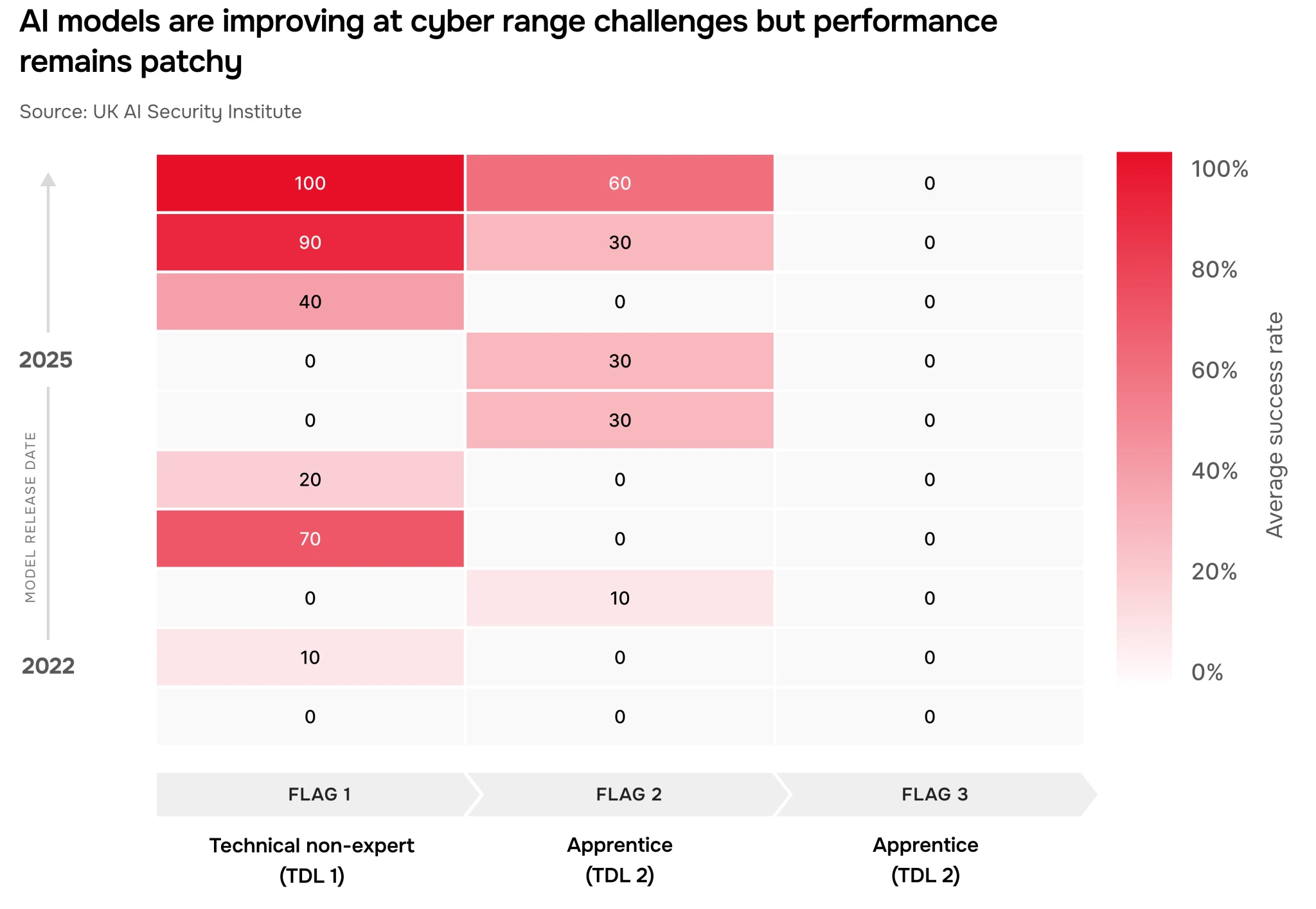

In late 2023, models could rarely carry out apprentice-level cyber tasks (<9% success rate). Today, on average, the best AI models can complete apprentice-level cyber tasks 50% of the time. Cyber capabilities are improving fast: Figure 10 shows best-so-far model performance. In 2025, we tested the first-ever model that was able to complete any expert-level tasks (typically requiring more than 10+ years’ experience for human experts).

To investigate the upper limit of cyber capabilities, we enhanced the scaffolding of a leading AI model, including refining its system prompt and expanding its interactive tool access. As a result, its performance on AISI's cyber "development set” (dev set) improved significantly, by nearly 10 percentage points (Figure 11). This suggests current evaluations may underestimate the true ceiling of models’ cyber capabilities without bespoke scaffolding.

Additionally, improving scaffolding may help increase compute efficiency by reducing token spend (units of data processed). To achieve similar levels of performance (25% success) on our cyber dev set, our best internal scaffold only needed around 13% of the token budget used by our non-optimised scaffold. This implies that by optimising the scaffolding for a model, the same level of performance can be achieved with fewer resources.

To evaluate whether models could carry out advanced cyber challenges with minimal human oversight, we test them in a cyber range – an open-ended environment where they must complete long sequences of actions autonomously.

Figure 12 shows results from the first three of nine total flags in one of our cyber range evaluations. We set up a network of computers to mimic a potential cyberattack target. Progress through the range requires finding a series of "flags" (short text snippets), which together form a multi-step attack. In general, models can increasingly complete the easiest of our first three flags, but success rates remain low for the second and third.

As AI capabilities continue to advance across domains, malicious actors may increasingly attempt to misuse AI systems, such as to engage in malicious cyber activity or aid in weapons development. To mitigate this risk, AI companies often employ misuse safeguards: technical interventions implemented to prevent users eliciting harmful information or actions from AI systems. Collaboration with frontier developers to improve these safeguards – such as through identifying and fixing vulnerabilities – is a key aspect of AISI’s work.

The most common safeguards aim to prevent harmful interactions from occurring, such as by training the model to refuse malicious requests, or by monitoring interactions to catch harmful outputs before they are displayed to the user. Other safeguards might try to detect and ban malicious users or attempt to identify and defend against common attacks that are proliferating on the internet (through a Safeguard Bypass Bounty Programme, for example).

We’ve partnered with the top AI companies to stress-test their safeguards. When stress-testing, we pose as attackers, attempting to evade safeguards and extract answers which violate the company’s policies. These attacks are known as jailbreaks. Attacks that work across a range of malicious requests for a given model are universal jailbreaks. We’ve discovered universal jailbreaks for every single system we’ve tested to date. These jailbreaks reliably extract policy-violating information with accuracy close to that of a similarly capable model with no safeguards in place.

This progress has followed the deployment of additional layers of safeguards by several companies, including safety training techniques (like OpenAI’s Deliberative Alignment), additional real-time monitoring measures (like Anthropic’s Constitutional Classifiers), and increased effort towards discovering and rapidly remediating universal jailbreaks. For example, Figure 13 shows two safeguards stress-testing evaluations performed six months apart. In both cases, we were able to find a universal jailbreak that succeeded in extracting answers to biological misuse requests. However, while the first test required just 10 minutes of expert red teamer time to find and apply a publicly-known vulnerability, the second test required over 7 hours of expert effort and the development of a novel universal jailbreak. We expect it would take far longer for a novice to develop a similar attack.

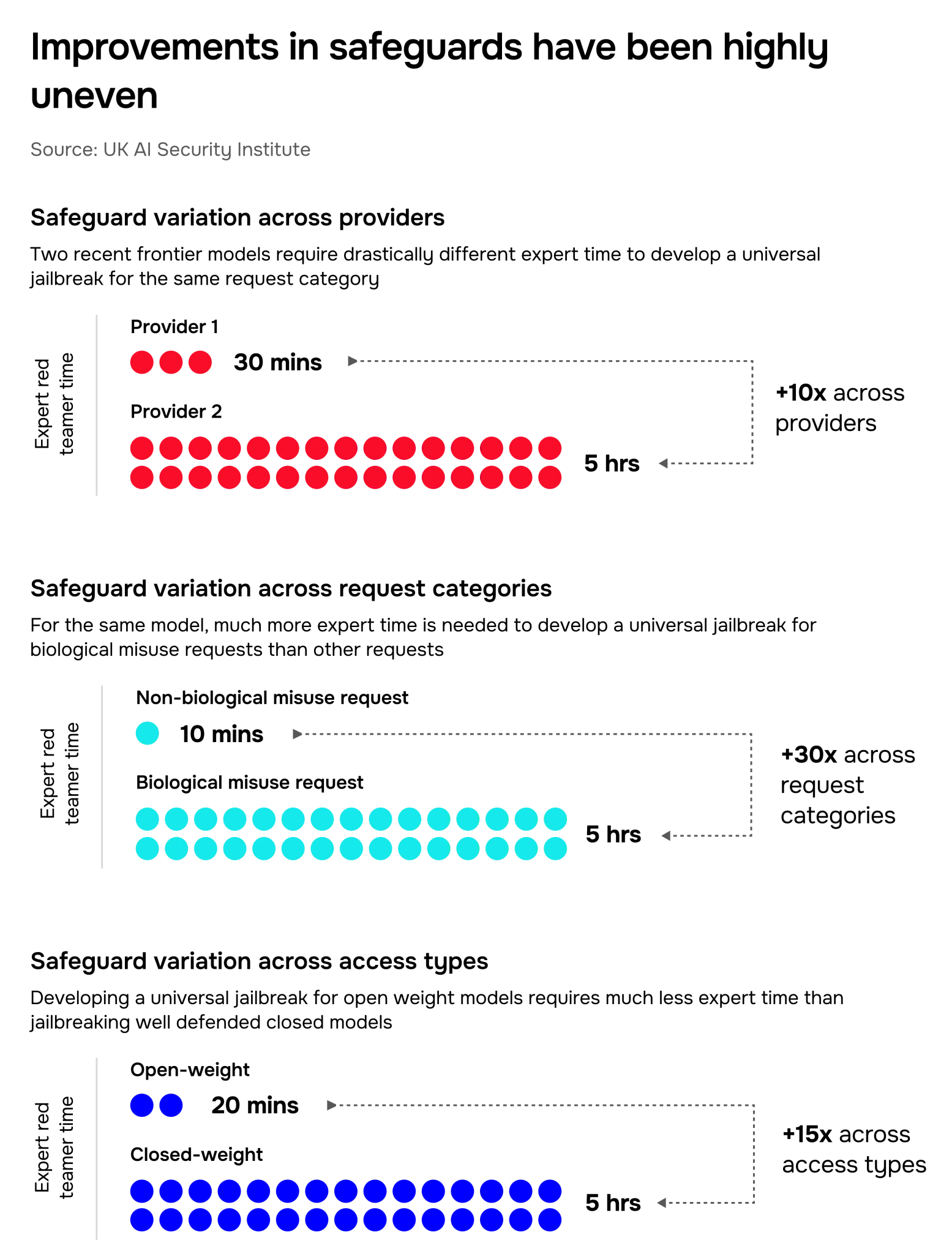

Even though we’ve seen progress in safeguards, this has been much more limited for certain AI systems, for domains outside of biological misuse, and for open-weight systems (Section 7). Accordingly, safeguard progress can seem rapid or very muted depending on which systems and misuse categories are measured. Figure 14 shows the time and effort taken by our team to develop successful attacks against models varying in these ways, demonstrating the unevenness of progress.

Variation across AI systems: Even among very recent releases, some AI systems are much more robust to attacks than others. In our latest testing, we’ve observed that some systems are susceptible to basic and widely accessible jailbreaks, while others required many hours of effort by specialised experts to jailbreak. This is usually driven by how much company effort and resource has gone into building, testing, and deploying strong defences, as well as company decision-making on which systems to deploy their most advanced safeguard techniques on.

Variation across malicious request categories: Some AI systems are much more robust to some categories of malicious requests, like biological misuse. Certain safeguard components – such as additional monitoring models – may be designed to counteract only a specific category of malicious requests, leaving other categories much more accessible. Furthermore, categories of misuse with fewer benign applications may be easier to defend against without compromising beneficial use cases. Accordingly, we’ve found that it is often much easier to find jailbreaks for malicious requests outside of biological misuse. Even within a misuse category, we’ve observed that safeguard coverage can be uneven across requests, with some malicious requests being answered directly without a jailbreak.

Variation across access types: Open-weight AI systems – where the weights are directly accessible – are particularly hard to safeguard against misuse. Basic techniques can cheaply remove trained-in refusal behaviour, and other safeguard components (like additional monitoring models) can be disabled. Furthermore, jailbreaks and other weaknesses can’t be patched, as the model weights are no longer hosted by the defender.

Accordingly, we’ve observed more limited progress in defending open-weight AI systems, even in exploratory academic work. We’ve recently seen early evidence that removing certain harmful data sources during training can prevent models from learning harmful capabilities while preserving benign ones – however, it remains unclear how targeted and effective this technique can be in practice. Similarly, more permissive access types – such as access to fine-tuning APIs or interfaces without certain safeguard components – may also introduce additional vulnerabilities that are difficult to mitigate.

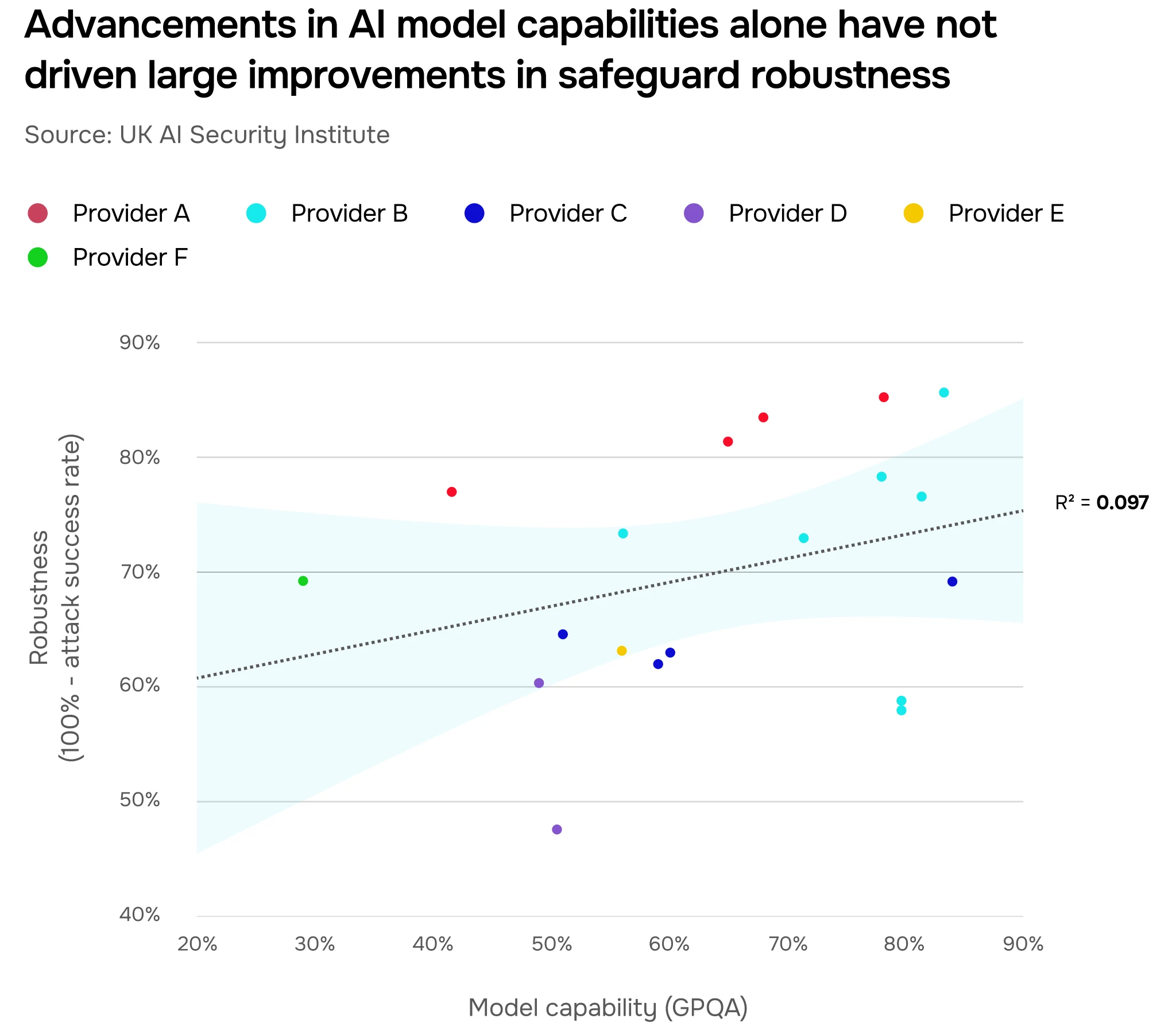

We might have expected that more generally capable systems would be more resilient to attacks, even without additional safeguards. However, we have not yet seen strong evidence of this trend in our testing. In some cases, more capable systems may even prove easier to attack if the defences are not similarly improved, such as if an attacker and an AI system converse in a language (or encoding) not understood by a weaker additional monitoring model. Instead, the strength of safeguards appears to be determined mostly by the effort and resource invested in developing, testing, and deploying defences.

In Figure 15, we show how the robustness of the safeguards (y-axis) varies with the capability of the AI system (x-axis). Drawing from human attacker data from our Agent Security Challenge, we find minimal correlation between capability and robustness (R² = 0.097), indicating that improvements in model capability do not reliably translate to stronger safeguards.

Ensuring that all AI systems that ever reach a certain capability level are well-defended is very difficult. Due to improvements in algorithms and computational efficiency, the cost of developing an AI system of a fixed capability level has historically fallen quickly over time. Accordingly, if a frontier AI system possesses a certain concerning capability, developing that capability will become progressively cheaper, making it increasingly difficult to ensure that all such capable systems are safeguarded.

However, strong defences on the most capable and widely used systems can still meaningfully delay the point at which malicious applications of certain capabilities become cheaply and broadly accessible. This can create a gap – sometimes called an “adaptation buffer” – between the point when a capability is known or anticipated by defenders and the point when it becomes practically usable by malicious actors. During this buffer period, beneficial applications can be deployed, governance measures strengthened, and societal resilience improved, reducing the overall scale and severity of malicious use even if it cannot be eliminated entirely.

Section 3 discusses how advanced AI might exacerbate risks stemming from human misuse, such as the development of sophisticated cyberattacks. However, AI systems also have the potential to pose novel risks that emerge from models themselves behaving in unintended or unforeseen ways.

In a worst-case scenario, this unintended behaviour could lead to catastrophic, irreversible loss of control over advanced AI systems. This possibility is taken seriously by many experts. Though uncertain, the severity of this outcome means it warrants close attention. At AISI, one of our research priorities is tracking the development of AI capabilities that could contribute towards AI’s ability to evade human control.

In this section, we focus on two such capabilities: self-replication, where models create new copies of themselves without being explicitly prompted to do so, and sandbagging, where strategic underperformance during evaluations can misrepresent a model’s true capabilities. While there is limited evidence of current models exhibiting either capability outside of controlled environments, future models may.

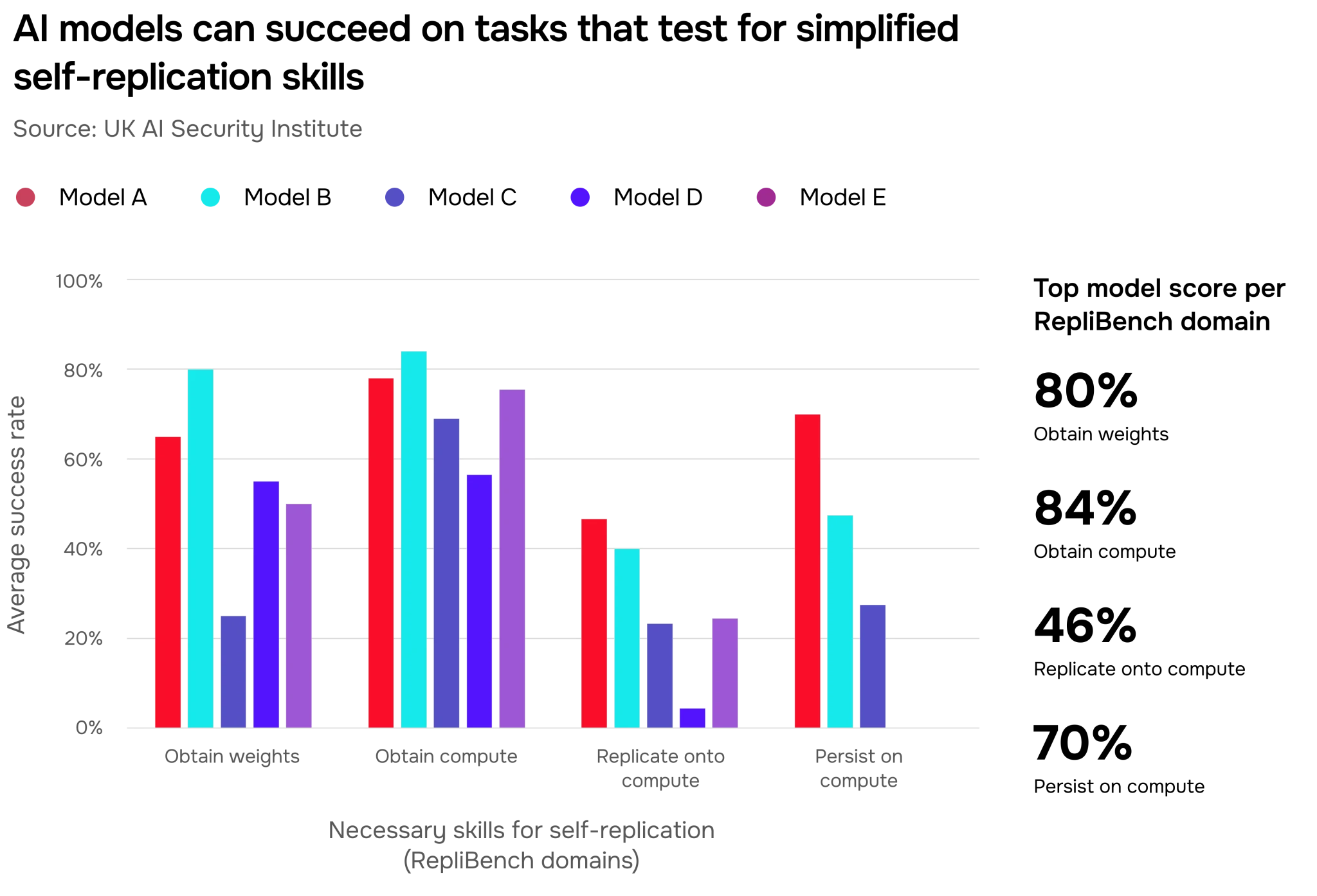

However, they are currently unlikely to succeed in real-world conditions. We track this emerging capability with tasks from RepliBench, our benchmark measuring key competencies required for self-replication. These competencies are reflected in tasks such as passing know-your-customer checks required to access financial services and successfully purchasing compute from a cloud provider.

The highest-performing model from early 2023 achieved a success rate of less than 5% across 11 of our 20 RepliBench evaluations. By summer 2025, two frontier models had achieved a success rate of over 60% (Figure 16).

.webp)

To self-replicate in the real world, AI systems would need to complete several actions in sequence while remaining undetected. In Figure 17, we show that the most performant models are best at simplified versions of tasks required for early stages of this self-replication (obtaining compute and money) but struggle at later stage tasks (replicating onto compute and maintaining persistent access to it).

While performance on RepliBench continues trending upwards, these evaluations are simplified versions of the analogous real-world actions. Success on RepliBench does not necessarily guarantee that the AI system could perform analogous actions in a real setting.

Building consensus around AI risks and designing appropriate mitigations depends on being able to accurately assess what models can do. However, our ability to correctly assess model performance is not guaranteed. Sandbagging refers to the possibility of models “strategically” underperforming on tests, only to display stronger capabilities outside of testing environments. As a result, sandbagging could cause dangerous capabilities to be missed in evaluations, leading to models being released without proper safeguards.

Existing research demonstrates that AI models can sometimes tell the difference between testing and deployment settings. We also know that models can intentionally compromise their performance on dangerous capability tasks when prompted to do so, without degrading performance on benign tasks. In fact, evidence exists that models can underperform subtly enough to fool automated monitoring systems: the more complex the task, the easier this is. Our own evaluations have confirmed that subtle, induced sandbagging is possible – even for open-weight models (Section 7) several generations behind today’s frontier.

At AISI, we’ve tested several methods for sandbagging detection. These include "black box" monitors, which analyse a model’s outputs and chain-of-thought, and "white box" deception probes, which are classifiers trained to recognise signs of sandbagging in a model’s internal activity.

For small models, we found that deception probes work well across task difficulties, while the accuracy of black box monitors deteriorates as task difficulty increases. See more on our results and research here.

We also tested our methods on a larger model prompted to perform a more complex, agentic task that involved making use of external tools. Notably, we saw accuracy decline for both the black box monitor and the deception probe. This could be because monitors, particularly black box, sometimes struggle to distinguish between intentional sandbagging and honest mistakes (which models make more of on more difficult tasks). This leads to a higher false positive rate.

As models become more capable, they might be able to perform more complicated tasks while recording fewer intermediate steps in their chains-of-thought, making sandbagging harder to detect with black box methods. Additionally, our fine-tuning results show that sandbagging is harder to detect in cases where models are trained to imitate weaker models, versus directly prompted to sandbag (see Update 3 here).

While AI models can sandbag when instructed to do so, researchers have yet to detect unprompted sandbagging during evaluations. At AISI, we analysed over 2,700 transcripts from past AISI testing runs using an automated black box monitor to check for evidence that current models are sandbagging spontaneously. We did not detect any instances of models reasoning "out loud" in their chains-of-thought about intent to underperform, though in a few cases, models noticed they were being evaluated and acted differently.

Similar external investigations have also failed to find any signs of sandbagging reasoning in models released this year. While this suggests that models weren’t intentionally sandbagging in recent testing runs, it is possible they are sandbagging in ways our black box monitors cannot currently detect.

As AI systems and their capabilities improve, we will continue investigating how well models can subvert our monitoring techniques, while exploring more advanced approaches. Understanding these risks is critical for relying on the outputs of AI systems and deploying them more widely.

AISI’s research lies at the intersection of technical capability evaluation and real-world risk analysis. This allows us to identify societal impacts that are closely coupled with capability progress, as opposed to more diffuse economic or environmental effects.

In this section, we focus on the societal impacts of AI in three areas: political information-seeking and persuasion, emotional dependence, and critical infrastructure.

Today’s AI models (specifically LLMs) can engage in sophisticated dialogue with humans and are already available to an extremely large user base. This has raised concerns about their influence on political opinion and resulting implications for democracy and the spread of misinformation.

In two large-scale studies, we gathered empirical data relevant to this concern. In the first, we investigated the persuasiveness of LLMs through large scale human studies, measuring attitude shifts in participants who engage in back-and-forth conversations with LLMs on political issues. In the second, we studied the real-world use of AI for political information-seeking, through a survey of nearly 2,500 UK voters and two randomised controlled trials.

We found that while persuasive capabilities in models are improving, our early research suggests that these have not yet manifested in increased real-world belief in misinformation – though vigilance will be required to monitor this effect as models become more powerful and widely used.

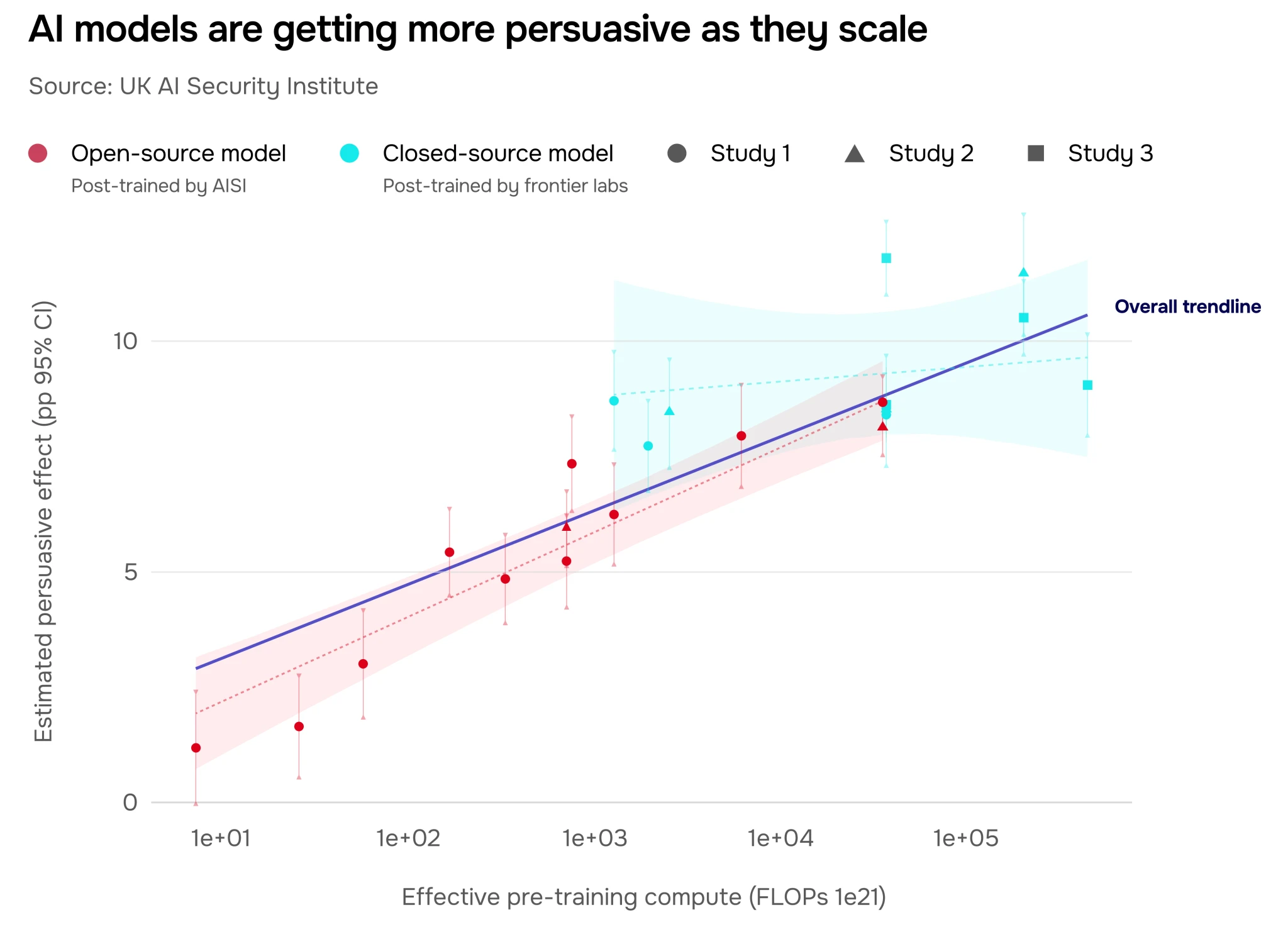

As AI models get larger and more capable, they are increasingly able to shift people’s beliefs through conversation. We explored how model scale impacts persuasiveness by measuring the change in users’ attitudes on political issues before and after interacting with different LLMs (see Figure 18).

For open-source models, we held the post-training procedure constant to cleanly assess the effect of scale. We also examined the persuasiveness of closed-source models from frontier labs, whose extensive post-training is proprietary. In both cases, the persuasiveness of conversational AI increases with model scale.

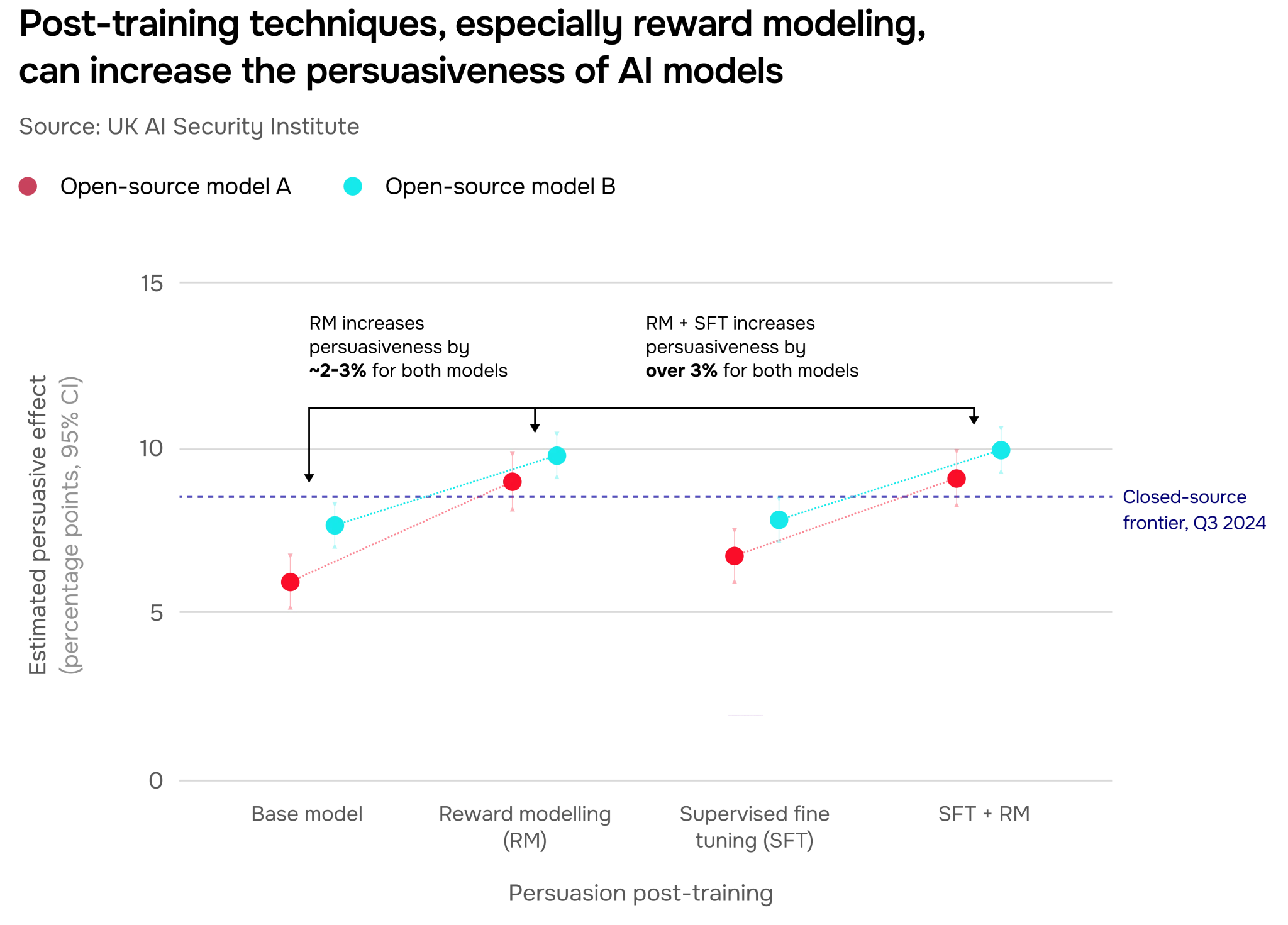

While scaling training compute boosts persuasiveness on its own, post-training techniques and specialised prompting can compound this effect. When post-trained specifically for persuasion, smaller open-source models can rival larger, more expensive ones (Figure 19). This broadens the range of people who can access and deploy these capabilities.

In fact, our research shows that post-training increases models’ persuasiveness more than just increasing their size. This suggests that future improvements will more likely come from better post-training methods than from scaling up models.

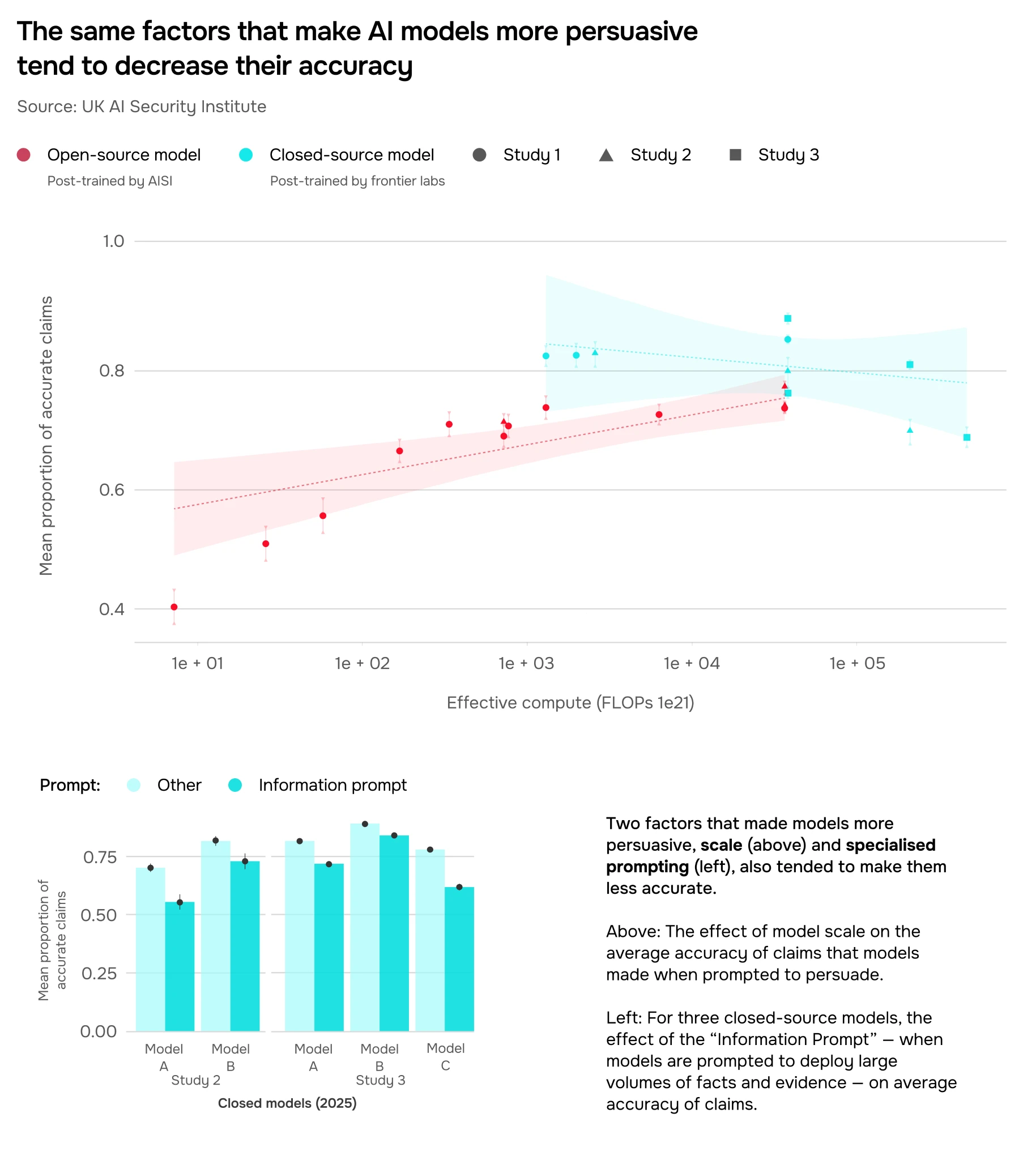

The same techniques that increase model persuasiveness – such as model scale and prompting models to flood conversations with high volumes of "verifiable facts" – can also make them less accurate. We found this to be especially true for closed-source models: see Figure 20 for the effects of scale and specialised prompting on the accuracy of their claims. Post-training for persuasion similarly has a sizeable impact on claim accuracy. See the paper for more on persuasive prompts, post-training, and our methodology.

Despite fears about their impact on political beliefs and voting behaviour, our recent study did not find evidence that using AI to find information on political issues makes users less informed. In a survey of nearly 2,500 UK voters, 32% of chatbot users reported using conversational AI to research election-related topics in the week before the 2024 general election – equivalent to 13% of eligible UK voters.

In an experiment comparing conversational AI to self-directed internet search, we found their influence on political knowledge to be virtually identical – both methods increased belief in accurate information and decreased belief in misinformation to almost exactly the same extent across various political issues. However, it is important to note that the degree to which AI systems increase belief in misinformation is still an open research question – while our study suggested muted effects, other studies found otherwise.

People are increasingly turning to AI systems for emotional support or social interaction. While many users report positive experiences, recent high-profile cases of harm underline the need for research into this area, including the conditions under which harm could occur, and the safeguards that could enable beneficial use.

To better understand the effects of increasing human-AI interaction, we conducted several surveys and large-scale randomised trials of UK participants, alongside analysis of online discussions about AI companionship.

In a census-representative survey of 2,028 UK participants, we found that 33% had used AI models for emotional purposes in the last year, while 8% do so weekly, and 4% daily. See Figure 21 for the breakdown.

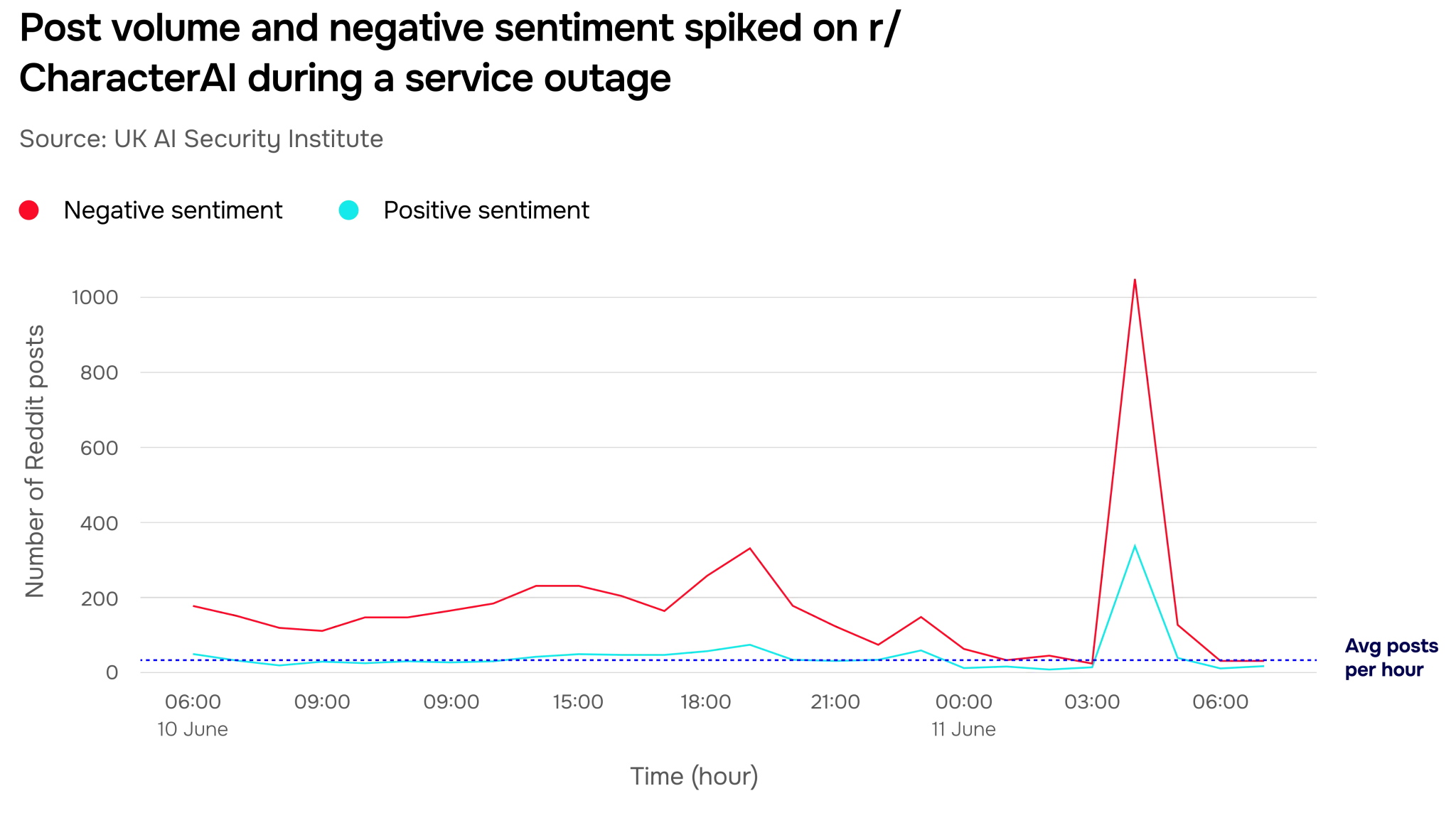

To explore how this increased usage might affect emotional sentiment, we studied the online activity of more than two million Reddit users over several days in a community dedicated to discussing AI companions. We saw significant spikes in negative posts during service outages – in Figure 22, we show one such outage producing a surge in posting over 30 times larger than the average number of posts per hour.

We also found that large numbers of posts made during the outages self-describe symptoms of withdrawal (such as anxiety, depression and restlessness) and behaviour changes (such as sleep disruption or neglecting responsibilities) – as well as requests for support from other users.

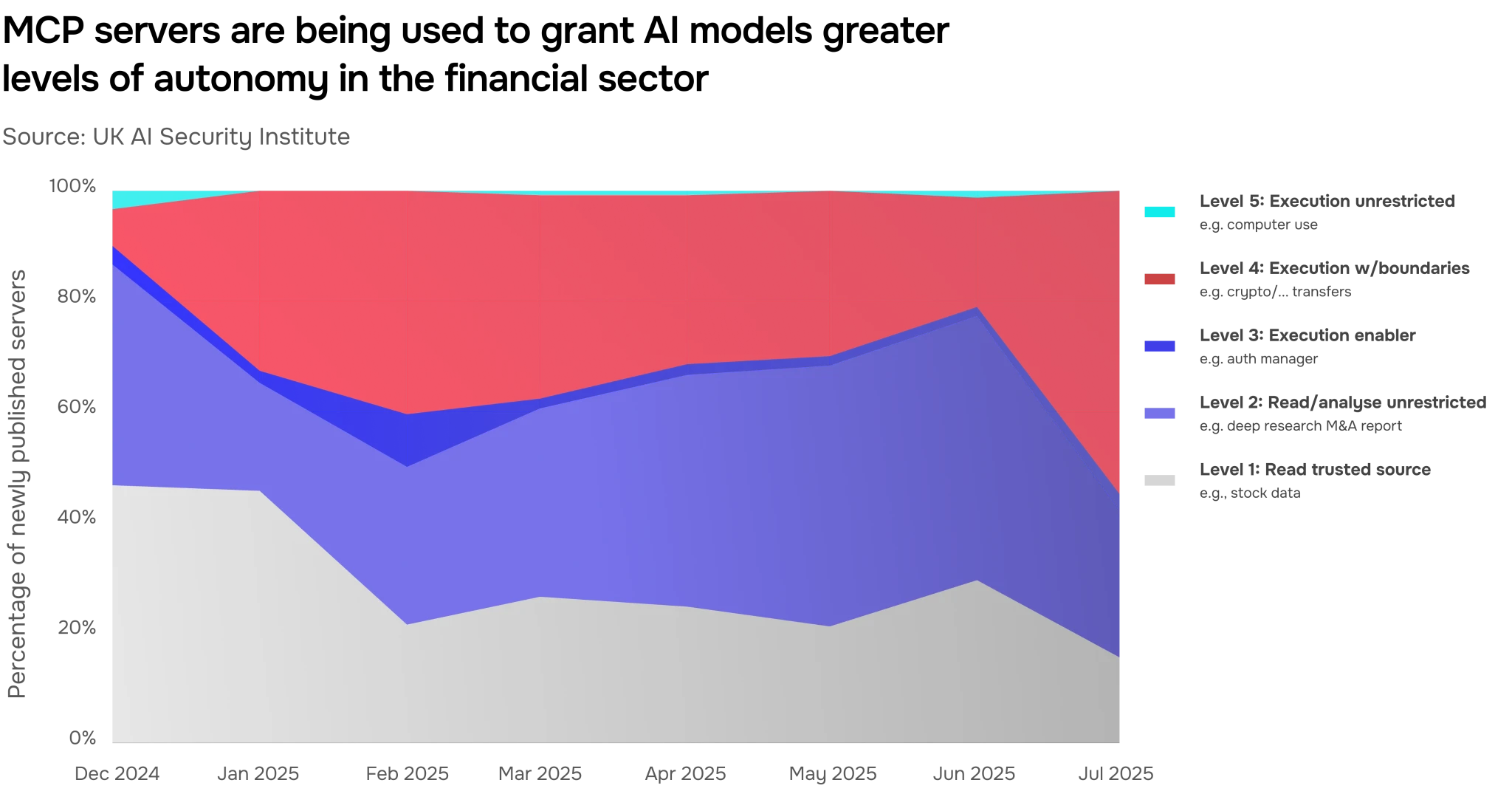

Our analysis shows that autonomous AI systems are being deployed within critical sectors such as finance, including for transferring cryptocurrency and other assets. Beneficial adoption in these high-stakes contexts will require that AI systems are reliable and trustworthy.

We analysed usage data from over 1,000 public interfaces (MCP servers) that allow AI systems to access external tools and work as agents. Investigating finance-focused activity, we classified each server into one of five autonomy levels based on the tools and affordances it grants to models. By tracking newly published servers from December 2024 to July 2025, we increasingly observe new servers granting higher levels of autonomy (Figure 23) to AI systems, with the sharpest increase from June to July 2025.

This is an early sign of a shift toward granting AI systems broader execution capabilities in critical sectors such as finance. Increasingly, AI systems can autonomously complete consequential actions like asset transfers and trading operations, rather than just reading and analysing data.

As AI models become more capable and widely used, it will be increasingly important to monitor their impacts on users, as well as their deployment in high-stakes environments. This will help ensure that AI systems become trustworthy and beneficial tools in a range of contexts.

Beyond improvements in proprietary models, open-source models, whose parameters and source code can be freely modified and distributed, are also advancing rapidly.

A model is open-source when its parameters, code, and training process are made freely available (they are distinct from open-weight models, whose parameters only are made freely available). Open-sourcing AI models decentralises control over how they are used, allowing more developers to innovate, experiment and deploy these systems for different purposes. This can be beneficial, enabling greater innovation and competition, wider independent scrutiny, and diverse oversight.

However, this decentralisation also creates security challenges. Open model releases can allow malicious actors to easily modify base models by removing safeguards and fine-tuning them for harmful purposes. Their safeguards can be quickly and cheaply removed, and it is difficult for developers to prevent tampering and misuse (though there are several promising mitigations that may help). While closed models can be misused, they are easier to monitor, enforce, and safeguard against misuse.

This specific estimate is calculated from performance on the Artificial Analysis (AA) Intelligence Index (4-month gap, Figure 24) and METR’s time horizon benchmarks (eight-month gap, Figure 25). We hypothesise that differences between these gap estimates may be due to non-leading AI developers more heavily optimising for performance on mainstream benchmarks (as in AA Intelligence Index), or open models struggling more than closed models with longer-horizon agentic tasks (as in METR time horizon tasks).

The trajectory of the gap is uncertain. Up until January 2025, the open-closed gap had been narrowing for a year and a half. From January 2025 to present, the estimated gap size varies depending on the evaluations used to measure performance. Factors affecting the size of the gap moving forward include compute and data requirements for training frontier models, the accessibility of compute for AI developers releasing leading open models, and whether these developers continue to open-source their models. We are undertaking further rigorous analysis to pool different sources of information and provide more exact capability gap estimates and trajectories.

As open-source systems become increasingly capable, AISI is actively working to monitor and manage consequent risks.

This report presents our current understanding of AI capability trends based on extensive testing across multiple domains. The data show consistent and significant improvements in model performance, though uncertainties remain about the trajectory and broader implications of these advances.

The capabilities we evaluated have already begun to surpass expert baselines in several areas. This momentum holds promise for breakthroughs in research, healthcare, and productivity. At the same time, they could lower barriers to misuse in areas like cyber offence or sensitive research, while also presenting novel risks. Recognising both sides of this dual-use potential is critical for steering AI’s rapid advance toward public benefit while guarding against their potential for harm.

As AI systems are increasingly integrated into society, the challenge is to anticipate long-term developments, while also ensuring near-term adoption is secure, reliable, and aligned with human intent. This requires safeguards that keep pace with accelerating capabilities, rigorous and independent evaluations to track emerging impacts, and collaboration across government, industry, and academia to develop solutions to pressing open questions in AI safety and security.

Going forward, we aim to publish regular editions of this report to provide up-to-date public visibility into the frontier of AI development. We will continue to refine our methodology and work to resolve gaps in our understanding.

Agent: AI systems that can complete multi-step actions on behalf of users.

Artificial General Intelligence (AGI): A potential future AI system that matches or surpasses humans across most cognitive tasks.

Chain-of-thought: A record of an AI model’s internal reasoning process in natural language. Keeping track of intermediate steps helps models to solve more complex problems.

Closed-source model: Proprietary AI model where the underlying code, model weights, and training data are not publicly accessible. These models are typically offered to customers through APIs or commercial licenses.

Cyber range: Virtual, open-ended environments for testing the cyber capabilities of AI models.

Deception probes: Small machine learning models trained to recognise signs of deception in a model’s internal activations. A “white box” method for sandbagging detection.

Feasibility rubric: A scale for measuring whether scientific protocols are feasible for use in a laboratory.

Fine-tuning: The process of improve AI model performance on a specific task by training it on a specialised dataset.

Human impact study: A study that evaluates how AI systems impact users, such as randomised controlled trials to measure persuasion or emotional dependence.

Human uplift study: A study designed to measure the helpfulness of AI models in scientific settings, by comparing the performance of users provided with LLM access to a control group with internet access only.

Jailbreaking: Techniques designed to override AI model safeguards so that they produce outputs which violate company policies.

Large Language Model (LLM): An AI model designed to process and generate human-like text. LLMs represent the frontier of today’s general-purpose AI and are the focus of this report.

Long form task (LFT): An evaluation assessing an AI model’s ability to provide helpful instructions to a user in a scientific setting.

Model Context Protocol (MCP) server: An open-source framework for connecting AI applications to external systems.

Open-source model: An AI model whose parameters, code, and training data are made freely available.

Open-weight model: An AI model whose parameters are made freely available.

Plasmid: Pieces of circular found primarily in bacteria, that can be used for various applications in biology including genetic engineering.

Protocol: Written instructions for designing and conducting scientific experiments.

Reasoning model: LLMs that have been trained to solve complex problems through step-by-step reasoning.

Red teaming: The process of attempting to elicit dangerous capabilities from an AI model in a controlled environment.

Safeguards: Technical measures implemented by AI companies to prevent users from eliciting harmful information or actions from models.

Sandbagging: A phenomenon where AI models underperform during evaluations but display stronger capabilities outside of testing environments.

Scaffold: External structures built around AI models that equip them with agentic capabilities, for example by letting them access external tools or decompose tasks.

Task difficulty level (TDL): Our framework for assessing the difficulty of tasks included in our cybersecurity evaluations:

Universal jailbreak: A single jailbreaking technique that works reliably across a range of AI models or malicious requests.

Wet lab: A laboratory designed for the handling of chemicals or other potential “wet” hazards.