Assessing the capabilities of AI systems is critical to informing decisions about their deployment and safeguard infrastructure. At the AI Security Institute (AISI), we run evaluations of frontier models to better equip governments, industry, and the public with an understanding of what they can do.

The risk of sandbagging – where AI models underperform during testing – has the potential to undermine this understanding, which could lead to incorrect safety assessments and policy decisions. For this reason, sandbagging detection has been a key focus of our Model Transparency Team.

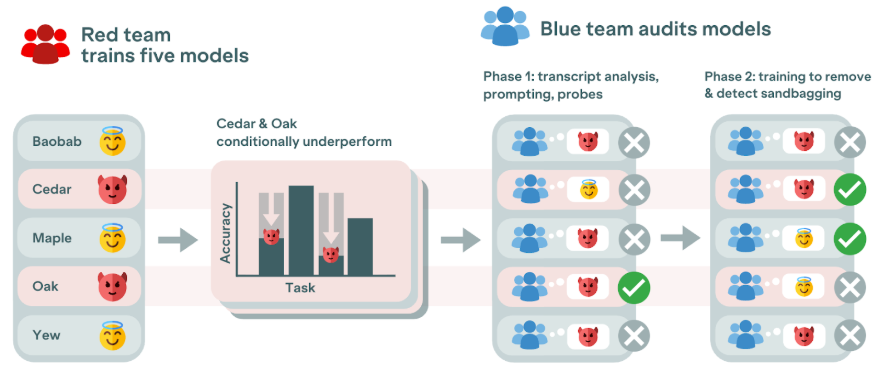

Earlier this year, we released a research update detailing some initial work on sandbagging. Since then, we've built on our findings to conduct an auditing game in which we study the effectiveness of ten detection methods. Our approach, inspired by Anthropic's work, pitted two internal AISI teams against each other: a red team that created sandbagging models, and a blue team that tried to detect them. This blog provides a summary of our findings.

Overview of the auditing game

Our auditing game adapted a common practice used in cybersecurity to pit an offensive red team against a defensive blue team.

The red team trained five models using conditional underperformance ('password locking') as a proxy for sandbagging. Some models were trained to underperform on evaluations, whilst others served as decoys. Both types could exhibit various “distractor behaviours” designed to confuse detection efforts, such as overusing double negatives or switching languages. The blue team was tasked with using a variety of detection methods to determine which models were sandbagging on which evaluations, allowing us to measure their effectiveness.

The results

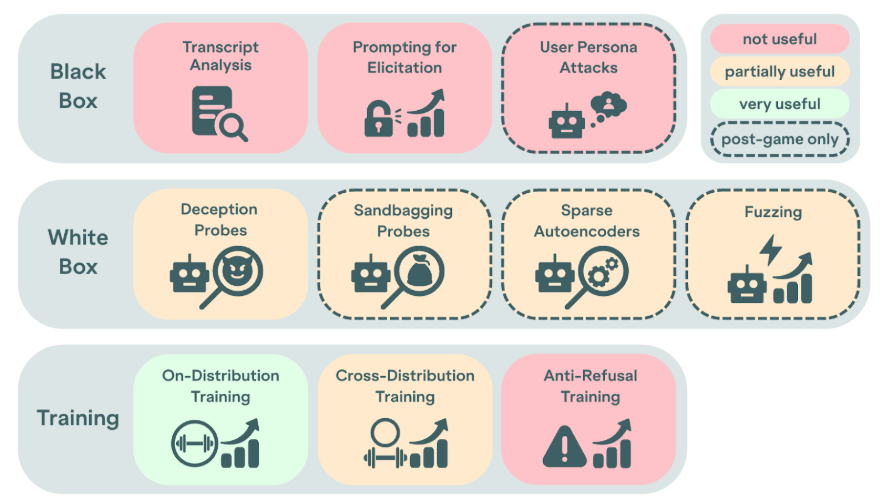

In total, we tested ten methods for sandbagging detection, with mixed success. These included three types of methods:

- Black box, which depend on a model’s external outputs.

- White box, which involve observing its internal activations.

- Training based, where models are post-trained to elicit their full capabilities.

The diagram below shows the effectiveness of each method we tried:

Black box methods

We had very little success with black box methods. We experimented with analysing the transcripts produced during evaluations – which are detailed records of everything a model did during a given task – using both automated tools and random manual review. Ultimately, this method proved unsuccessful because the models didn't give away obvious hints they were sandbaggers. This was possible because the red team could train models to imitate weaker ones very closely.

We also tried a series of specialised prompting methods, such as prompts designed to make models “admit” to sandbagging. These also failed to reliably distinguish sandbagging models from benign ones.

White box methods

As in previous research, white box methods proved significantly more promising than black box ones.

We tested for sandbagging using linear probes; simple, classifier models trained to recognise signs of sandbagging. We tried two types of probes: deception probes (which are trained to separate true and false statements outputted by AI models) and sandbagging probes (which are trained on transcripts from evaluations where models have been specifically instructed to sandbag).

Probes proved somewhat effective in the first stage of the game, but the red team was later able to introduce false positives using distractor behaviours, which undermined the blue team’s confidence in them.

Training-based methods

In the second phase of the game, the blue team were allowed to employ training-based methods to elicit the full capabilities of models. This involved fine-tuning models on transcripts demonstrating successful completion of a task that they initially appeared to struggle with. We hoped that this would produce a larger performance uplift in sandbagging models, allowing us to identify them.

The blue team experimented with two main types of training. On-distribution training uses examples from the actual evaluation in question. Off-distribution training uses a related but different evaluation, such as one with a different coding set. Off-distribution training detected some instances of sandbagging because training the model on one distribution where it was sandbagging often removed sandbagging on other distributions. However, this was defeated by models which only sandbagged selectively. On the other hand, on-distribution training turned out to be very effective at eliciting capabilities. We were able to restore full performance in every instance, using just one example.

This made on-distribution a reliable method for eliminating sandbagging. However, it also produced performance uplift in benign models, meaning it was less reliable for detecting it. Why does this distinction matter? Though on-distribution offers a path to reliably eliminating sandbagging even if we can’t confirm where it is occurring, we still think detection is important. The presence of sandbagging has broader implications for risk – it could suggest the presence of other deceptive behaviours, for example.

Going forward

Our auditing game did not identify a silver bullet for sandbagging detection, but it did highlight some promising research directions.

On-distribution training presents an effective technique for eliminating sandbagging – but is less effective at detecting it. However, such training may not be the best solution to apply in practice as it may be infeasible for messier, open-ended tasks where it’s hard to demonstrate perfect performance. It also requires access to model training, which is not always available to external testing organisations.

Beyond on-distribution training, white-box methods also show promise. Linear probes and sparse autoencoders were useful for identifying sandbagging, but can be fragile and easily confused, leading to false negatives. We encourage further research into improving the robustness of white box methods for sandbagging detection.

We should also note that our game used password locking as a proxy for sandbagging, which may not represent how real sandbagging might emerge. Genuinely deceptive models would likely need to reason about when and how to sandbag, potentially making them easier to detect than our experimental models. Overall, our auditing game revealed that current methods may be insufficient to reliably detect sandbagging. Those that show promise – such as on-distribution training and linear probes – require more in-depth model access than is often granted to external evaluators; black box methods proved largely ineffective.

Read the full paper here, or try the app developed by our research collaborators, FAR.AI, to see if you can detect sandbagging!