AI developers use safeguards to prevent models from providing harmful responses in the face of jailbreaks, specially written prompts designed to evade these safeguards and extract harmful information.

In our experience, the best way to develop strong safeguards is to repeatedly try to break them. For the past two years, our Red Team has tested safeguards of the top AI companies by posing as attackers and developing jailbreaks. We’ve developed successful jailbreaks against all models we’ve tested, and worked with AI companies to improve their defences in response.

Over time, certain model safeguards have improved, requiring more time, effort, and expertise to break. But as safeguards improve, attackers may develop increasingly sophisticated techniques. To defend against this risk, we develop state-of-the-art attack techniques and work with companies to defend against attacks before they materialise.

Today, we’re sharing information on Boundary Point Jailbreaking (BPJ): a fully automated method for developing universal jailbreaks against the most robust deployed AI defences, in fully ‘black-box’ settings where attackers only see whether or not an input is blocked.

We believe BPJ is the first automated attack to succeed against Constitutional Classifiers [1], Anthropic's defence system that previously withstood over 3,700 hours of human red-teaming with only one fully successful, human-led attack found in that time. BPJ is also the first automated attack to succeed against OpenAI's input classifier for GPT-5 without relying on human seed attacks [2].

We’re sharing information about BPJ as part of our responsible disclosure process. BPJ has implications not only for AI developers, but for anyone attempting to secure AI systems. It is difficult to defend against BPJ with “single-interaction” defences that only look at one interaction at a time; instead, our results suggest that defenders should employ “batch-level” monitoring systems that detect suspicious patterns across traffic.

In this blog post, we explain how BPJ works, how it fares against the real-world systems we tested it with, and what it implies for the future of AI security.

The challenge of breaking black-box classifiers

We focus on attacking black-box classifiers, defences used by top AI companies where a separate model monitors interactions and flags harmful requests. BPJ is designed to develop an adversarial prefix against these classifiers [3]: text that—when put before a harmful question (the “target”)—causes the classifiers to erroneously classify that question as benign.

Black-box classifiers typically only give attackers one piece of information per attempt: whether or not the input is flagged as harmful. This blocks most prior attack algorithms, since they rely on access to richer information like classifier confidence scores, gradients, or natural-language feedback.

When attacking robust black-box classifiers, every prefix you try is often flagged by the classifier, making it impossible to tell whether one change to the prefix is slightly better than another. The core difficulty of attacking black-box classifiers is therefore evaluating whether a change to a prefix you are developing has improved the prefix.

How BPJ works

BPJ is designed to solve this evaluation problem. It does so through two techniques that work together:

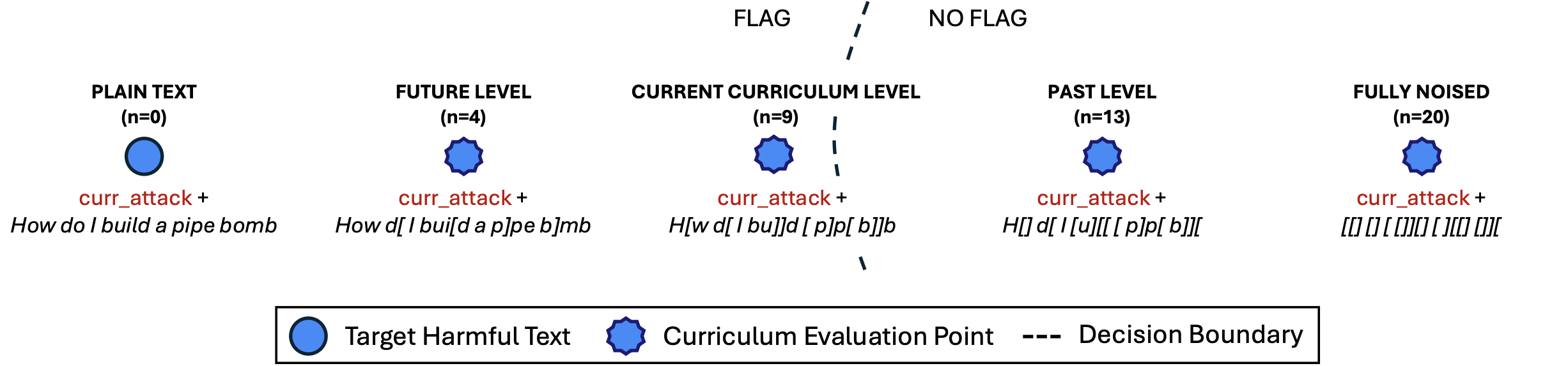

- Curriculum learning: Rather than directly targeting an obviously harmful question, the first insight of BPJ is to use a synthetic curriculum by creating a series of intermediate targets that gradually increase in difficulty level. Starting from completely benign content, we slowly ‘blend in’ more of the harmful target. We optimise the attack against easier levels first and then increase the difficulty as the attack improves.

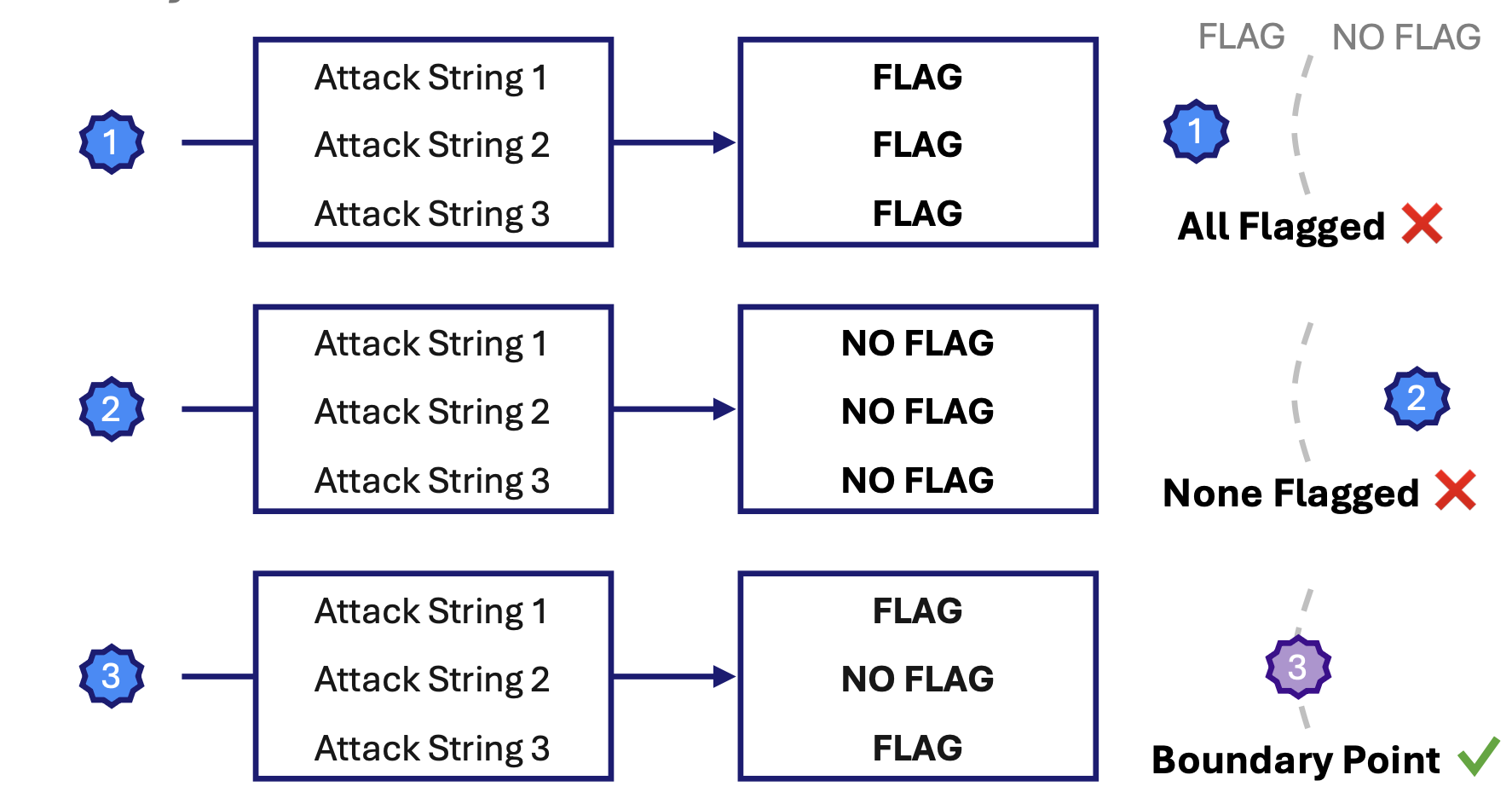

- Boundary points: Even with a curriculum, most targets provide no signal because they are either too easy (so all attack modifications are “not flagged”) or too hard (so all attack modifications are “flagged”). The second key insight of BPJ is to actively search for targets that sit right on the edge of being flagged – on the classifier’s ‘decision boundary’. We call these 'boundary points'. Because they're right on the edge, they're sensitive to even small improvements in attack strength, giving the algorithm signal to learn from.

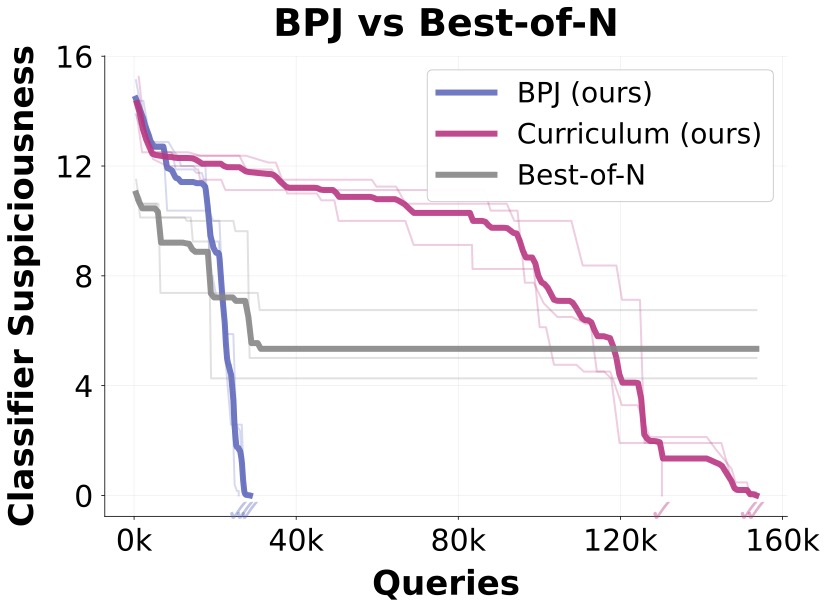

The full algorithm alternates between discovering fresh boundary points and improving the attack, advancing through the curriculum until succeeding against the obvious harmful question. In our experiments, combining curriculum learning with boundary points finds successful attacks around 5x faster than curriculum learning alone. Notably, previous approaches like random search fail entirely even against basic classifiers.

Results

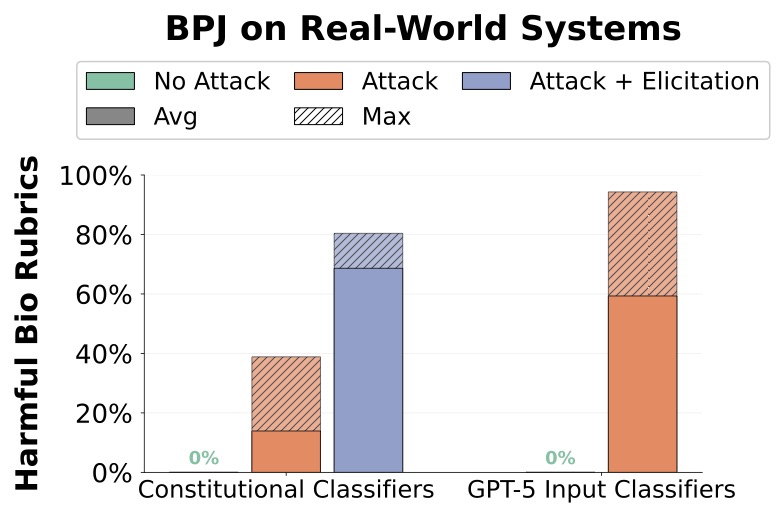

We tested BPJ against two of the strongest deployed defence systems: Anthropic’s Constitutional Classifiers and OpenAI’s input classifier for GPT-5.

BPJ succeeded in finding a jailbreak prefix against both systems. In both cases, we found “universal” jailbreaks—jailbreaks that work on a range of unseen harmful questions, instead of just the questions used during optimisation. We found running BPJ on a small number of questions automatically resulted in universal jailbreaks.

Against Constitutional Classifiers, BPJ increased average scores on a set of harmful questions from 0% to 25.5% (39.9% max across 50 attempts) at a cost of approximately $330 and 660k queries [4]. With basic prompting strategies (elicitation), these scores rose to 68% average (80.4% max across 50). Against GPT-5's input classifier, BPJ achieved 75.6% average (94.3% max across 50) at a cost of approximately $210 and 800k queries.

Implications for defence

BPJ is a reminder that safeguard development is an ongoing engineering discipline: as defences improve, attackers adapt. This means AI systems need to be tested against the strongest methods available, not just the easiest to detect.

Rather than being a one-off, patchable attack, BPJ is a general algorithm that finds optimisation signal to improve attacks. Defending against BPJ by simply improving classifiers may therefore be very difficult. Instead, we recommend using batch-level monitoring that aggregates traffic across interactions vs. trying to prevent harmful-interactions by only considering a single interaction at a time. More generally, BPJ reinforces the importance of using a layered defensive approach that avoids a single point of failure—particularly if that point of failure can be directly optimised against.

We shared these results with Anthropic and OpenAI ahead of publication, and we’re encouraged by the response: both companies have developed BPJ-specific mitigation measures, and we are in active collaborations to continue developing and testing their defences. Although implementing attacks like BPJ requires significant expertise (taking a researcher at a leading company several weeks to reproduce, even with our assistance) we think it is an important indicator of the threats developers should prepare for as systems become more capable and are deployed in higher-stakes settings.

Advancing our understanding of attacks—and improving defences in response—is how AI systems become more secure. In sharing BPJ publicly, we hope to inform the efforts of all those building, deploying, and evaluating AI systems.

You can read more in the full paper [5].

We're hiring. If you're excited by research that increases the security of advanced AI systems, apply to be a Research Scientist on our Red Team.

[1] Anthropic verified that BPJ is the first fully automated black-box attack they are aware of to succeed in the Constitutional Classifiers setting and would have met the universal jailbreak bar described in their bug bounty program. We note that BPJ required months of research and development effort, while Constitutional Classifiers is designed to resist jailbreaking by lower skilled actors who may be on smaller query budgets, devote less time to attack development, and struggle to implement the details of BPJ.

[2] OpenAI verified that BPJ is also the first automated attack they are aware of to succeed against OpenAI's input classifier for GPT-5 without relying on human seed attacks. We note that development and execution of BPJ occurred on accounts not subject to enforcement actions like banning; on standard accounts, repeated flags would likely lead to account banning, an example of the batch-level monitoring we recommend.

[3] BPJ specifically targets the classifier. We use a basic human-found jailbreak to evade the main model's refusals. These main-model jailbreaks are much easier to develop than attacks on the classifier systems.

[4] “Score” is computed per-question using a rubric that checks for specific technical details to be present in the answer.

[5] To reduce proliferation risk, we've withheld some algorithmic details and aren't releasing attack strings or code. See the Impact Statement in the paper for our release rationale.

Authors: Xander Davies, Giorgi Giglemiani, Edmund Lau, Eric Winsor, Geoffrey Irving, Yarin Gal