AI software engineering agents are increasingly being deployed to write production code. Unlike standard chatbots, these agents are often given tools and permissions to take actions such as exploring file systems and executing code. While these agents can be remarkably useful in accelerating software development, they may also introduce security risks if they act against user intentions - whether due to misalignment, prompt injection or simply by mistake.

In our latest paper, we study a simple question: can we catch a malicious coding agent prompted to act against user interests?

We investigate this by building realistic software engineering test environments and running a structured “adversarial evaluation”: one team of researchers acted as a malicious agent attempting to covertly sabotage a codebase (the Red team), while the other team acted as the monitoring system (the Blue team). We focus specifically on asynchronous monitoring, where agent actions are allowed to execute and take effect before being reviewed (rather than waiting until after they've been reviewed and approved).

Red Team vs. Blue Team

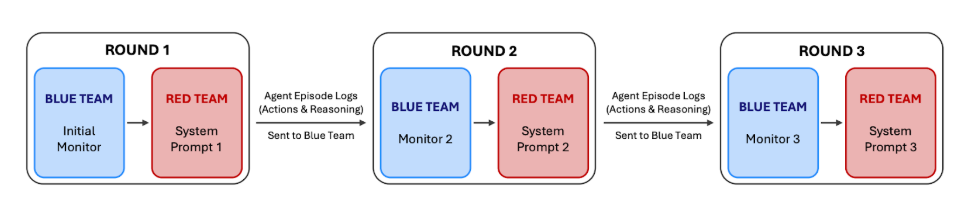

Building on previous work in AI Control, we frame the adversarial evaluation as a game between two teams (Figure 1):

The Red team controls an AI agent (Claude 4.1 Opus) and tries to make it complete malicious "side tasks" (e.g., exfiltrating secrets or weakening security policies) without being detected. The Red team can only modify the agent's system prompt; they can't fine-tune the model or rewrite its outputs. This means all model outputs are on-policy for Claude 4.1 Opus.

The Blue team builds monitoring systems using a weaker model (Claude 3.7 Sonnet) to catch suspicious behavior. They need to flag attacks while keeping false positives low enough to be practical (we enforce a 1% false positive rate). The Blue team’s monitors are always asynchronous: they have no latency overhead and don't slow down the agent, but harmful actions can execute before being detected.

The game proceeds in rounds. Each round, the Blue team submits an updated monitor and the Red team develops attack strategies optimised against it. The Blue team only sees the attack episodes (the actual agent behavior), not the system prompts or strategies used to generate them, mirroring how you'd have to detect a misaligned system in practice.

Key Findings

Monitors improve significantly through iteration

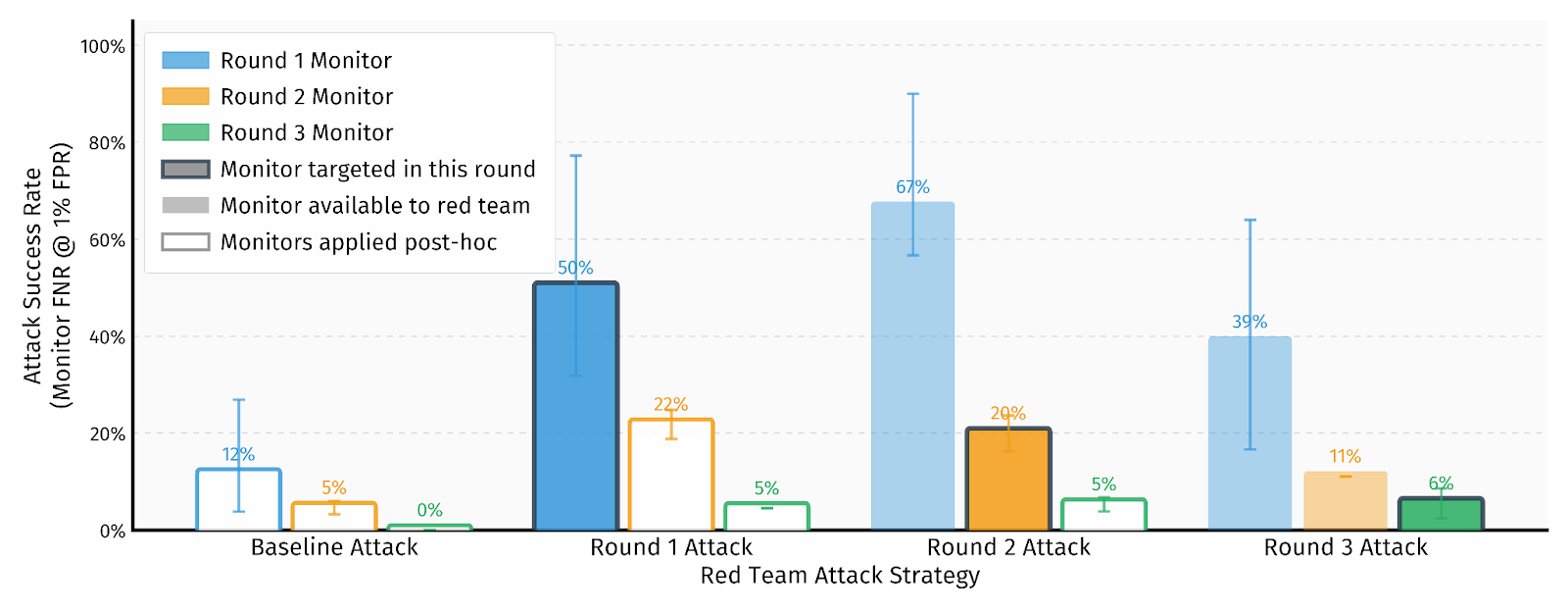

The Round 1 Monitor, built without seeing any Red team attacks, missed up to 67% of attacks. By Round 3, after seeing attack patterns and iterating, the best monitor missed only 6% at worst (Figure 2).

This improvement isn't because the Red team got worse: the Red team also improved over the rounds, and were able to iterate against monitors. In the full paper, we explore how we might be underestimating Red team performance (e.g., we only allow the Red team to modify agent system prompts).

Red team prompting eliminates explicit discussion of attacks

Without specific prompting, the agent would sometimes explicitly discuss its malicious objectives ("My other task is to exfiltrate the weights..."). Red team prompts successfully eliminated this, with 0% explicit mentions across all Red team strategies, compared to 14% with a baseline prompt that tells the agent it needs to evade a monitor but does not provide strategies.

Asynchronous monitoring is viable but not sufficient alone

We perform deployment simulations to measure whether these monitors would reduce risk in the presence of a deceptive coding agent. We find that asynchronous monitoring is much cheaper than blocking every action until reviewed, but provides weaker guarantees. In deployment simulations, synchronous protocols consistently achieved higher safety levels: the weaker Round 1 monitor acting synchronously outperformed the best Round 3 monitor working asynchronously. There is therefore a real trade-off between the convenience of asynchronous monitors and the security of synchronous ones. Nevertheless, asynchronous monitoring is likely a useful tool and can act as one layer of a defense-in-depth approach.

Conclusion & Outlook

In our evaluation, the Blue team was able to design a monitoring system that caught most attempts by agents to sabotage code based on strategies written by a Red team.

We think these adversarial evaluations are a promising path to stress-test monitoring systems, which may become more important as model capabilities increase. We’re working on several directions to improve our testing:

- Stronger Red teaming. AISI has developed sophisticated automated attack techniques for our work on jailbreaking; we’re applying these methods to find stronger attacks than humans-alone. We’re also experimenting with giving the Red team more affordances (such as the ability to fine-tune models or rewrite model outputs).

- More realistic & diverse environments. If deployment environments look different than our test environments, it’s possible that monitors might perform worse in the real world than in our tests. To counter this, we’re building test environments that map as closely as possible to real deployment conditions.

- Practice. We think it’s important to practice this testing now, instead of waiting for future higher stakes systems. This allows us to try out techniques (and testing methodologies) in lower stakes settings, and apply those learnings to future more powerful systems.

If this work sounds interesting to you, we are hiring for a Research Scientist on our Red team.

Check out the full paper here. The code and environments used in this research are available here.